In this conversation, Jonathan Ilicki and I explore topics like entrepreneurship and innovation in healthcare, the role of luck in scientific discovery, government's impact on medical progress, and the complexities of different healthcare systems. We discuss regulatory challenges and the potential of AI to improve healthcare, misconceptions about healthcare, the influence of "Big Pharma," and the drivers behind rising healthcare costs. Ilicki's deep insights and nuanced understanding of the healthcare landscape and technology will improve your thinking on these topics, as it did mine.

Jonathan is also writing on Substack about technology and healthcare; his excellent publication is called “Emmetropia,” and I recommend you subscribe!

The following is an amended version of the interview transcript that’s been edited for brevity and clarity. I’ve also included the audio recording of the conversation that you can listen to as a podcast. The audio quality is pretty good, but don’t expect a professionally edited recording. In any case, if you prefer listening over reading, it’s a great option.

Philip Skogsberg: You have a very eclectic background; you practiced medicine for a few years, and now you're an investor. Why don't you tell us a little bit about how you ended up where you are now?

Jonathan Ilicki: I first studied medicine and fell in love with it. It's rewarding to find a science that translates into something meaningful and intellectually challenging. However, while working clinically, I started encountering different kinds of system errors and wondered how people just accepted this. Why doesn’t someone fix it? You don't learn a lot about management or organization in med school. So, I did a business degree at the Stockholm School of Economics while working as a junior physician. That opened my eyes to structures and principles affecting healthcare beyond what medicine teaches. Eventually, my journey took me back to healthcare, where, starting off with an internship, I was involved in various change projects and realized how tricky it was to drive change in healthcare - who would have thought!? This experience led me to a Fellowship in Clinical Innovation, which in turn led me to co-found a startup, and this is also how we first met.

I continued with the startup and began my residency in Internal Medicine and Emergency Medicine, realizing the importance of practical experience in both medicine and business. I paused my residency to explore management consulting, which was extremely rewarding and high-paced. However, a former colleague convinced me of the potential in digitalizing healthcare, leading me to join Platform24 [a digital healthcare platform]. For the past five to six years, I've also helped various startups and scale-ups, applying lessons learned across different segments and within MedTech, healthtech, and life sciences. Recently, I joined Industrifonden, an evergreen Venture Capital fund in Stockholm, focusing on life sciences and a broad range of technologies relating to healthcare.

Philip Skogsberg: Have you been part of funding any companies so far?

Jonathan Ilicki: I just started three and a half months ago, so no, not yet. But something I’ve thought about recently is feedback loops. In medicine and in company building, feedback loops can be relatively short, offering learning opportunities based on observable outcomes. However, investing typically requires waiting years or decades to learn from real outcomes. So, I’ve been thinking a lot about how you can ensure that you're doing the right things in the right way when the actual outcome is so far away in time. How do you draw the right lessons?

Philip Skogsberg: Yeah, I thought about that a lot. I don't really have any clear answers, to be honest, but I do think that on a personal level, it’s not enough just to experience a lot of things, you also need to reflect on your experiences actively to learn from them. Organizationally, companies can have truth-seeking practices in place to ensure they’re learning the right lessons, too. Often, we draw lessons from outcomes intuitively without fully analyzing the accuracy of those lessons. So, it's important not to rely solely on initial hunches but to seek feedback and think critically about our conclusions.

Jonathan Ilicki: Indeed, finding ways to devise heuristics and processes ensures we draw the right conclusions from our experiences.

Philip Skogsberg: Speaking of lessons, what are some you've learned over the past decade or so about entrepreneurship?

Jonathan Ilicki: Ten years ago, I think I underestimated the value of entrepreneurship for societal progress. I grew up in a context where the idea of entrepreneurship as a job wasn’t talked about that much. Most people just ended up getting regular jobs. But at some point, I started realizing that all these things that surround us are the result of someone thinking about a problem and wanting to solve it; let me make a better sofa, a better chair, a better microphone, and so on. So I think that many people might take the products of entrepreneurship for granted.

Additionally, entrepreneurship involves a unique risk-bearing mechanism, which, while not always paying off for individuals, plays a crucial role in societal development and innovation. This asymmetrical risk distribution encourages talented individuals to pursue ventures with uncertain outcomes but with the potential for high rewards, which contributes significantly to technological and societal progress overall.

Philip Skogsberg: That’s an interesting way to put it. Most entrepreneurs probably don’t think about themselves like that. As an entrepreneur, on a personal level, you tend to be quite optimistic and even naïve. You’re unphased by very bad statistical odds don’t matter and just do what you need or want to do anyway. So, I agree that this model, while being very risky for individuals, is essential for innovation and progress.

Jonathan Ilicki: Exactly. The entrepreneurial model leverages individuals’ optimism and risk-taking, and this eventually leads to significant advancements for society. I think we wouldn't be here as a society if there weren't this naivité, some people being convinced that their venture is the one that will make it. It's the same thing with drug development. It's really expensive to develop new drugs; some cost literally billions of dollars. Even when you’ve come really far in developing some particular new molecule, doing in-vitro studies and animal studies, and are starting phase one trials - Even then, when we’ve already pumped in tens or hundreds of millions of dollars, 93% of those drugs will fail. But we need these naïve scientists and entrepreneurs who believe that their particular molecule will make it. Because ever so often, they're correct. And then they will change the history of healthcare and humanity.

Philip Skogsberg: What role does luck play in scientific progress and research?

Jonathan Ilicki: I think it plays a large role. There's a great book called "Chase, Chance and Creativity," written by a researcher [James H. Austin] who discusses his research and reflects at length on how luck has played a large role in his discoveries. He shares an anecdote - where his dog getting an inflammation leads him to a hypothesis that greatly accelerates his research. It's a clear example of how serendipitous moments can lead to significant breakthroughs, not just in science but with innovation at large. Beyond the anecdotal, the scientific process is often influenced by unforeseen factors and happy accidents that guide researchers toward new insights or hypotheses.

In science, there’s a lot of selection and publication bias around what gets published. There’s lots of Industry bias in terms of what companies publish. This is all noise that hides actual signals. But then, despite all this noise existing in the background data, someone eventually sees it from a certain perspective, which turns out to be the right way. So I think there's both luck in what leads people to pursue a certain path or certain hypothesis but also in what causes people to look at a problem from a certain perspective, which turns out to be the most effective way of looking at that problem.

Philip Skogsberg: What role does the government have in innovation and technological or medical progress? For example, we've had things like the Human Genome Project, the Apollo program, and big government-funded projects like that. People put different weights on the impact that they have had on human progress, technology, and society overall. Where do you come down on that?

Jonathan Ilicki: I think the government's involvement is crucial, not just in funding but also in fostering an environment where innovation can thrive.

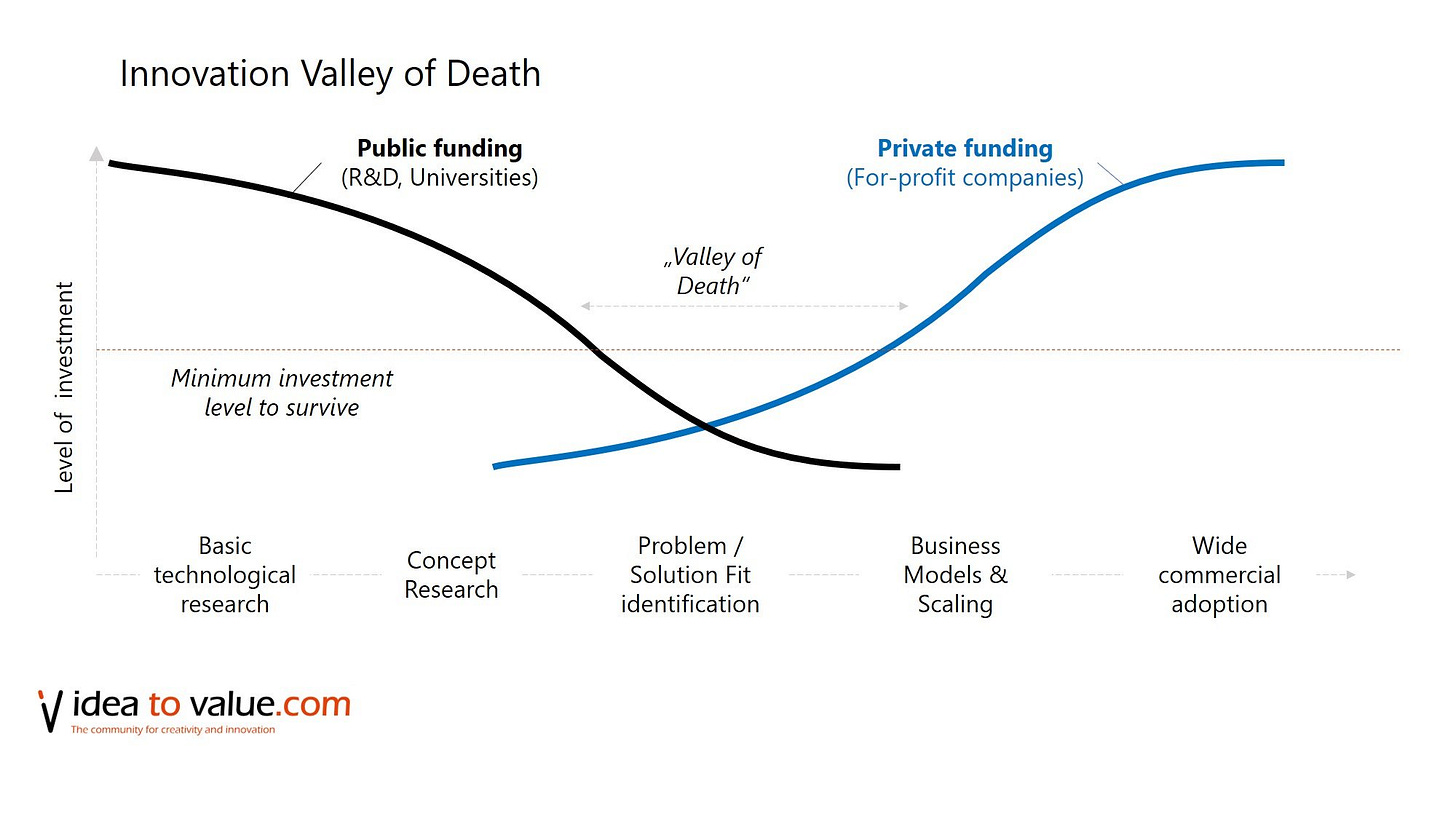

There’s this concept of the “triple helix”, which is a fancy name for when academia, industry, and government collaborate, and I think this is critical for fostering innovation. This collaboration can help innovators navigate the "valleys of death" that many ideas face when moving from concept to reality. The phase where it’s hard to get something off the ground. There’s a gap here where venture capital doesn’t always work well because there aren’t strong enough incentives to fund projects without clear commercial paths.

So, I believe there's a need for a third party to make it easier for ideas to get to the next level of development. However, the effectiveness of government involvement can vary by context. In Sweden, for instance, there’s this thing where researchers working for a research center or lab, per default, own the IP they create, which leads to a unique dynamic and different incentives for creating products or companies compared to other countries. So, overall, I think the role of government in innovation is vital, but its impact can differ based on the regulatory and operational landscape.

Philip Skogsberg: There are plenty of conspiracy theories and sometimes just confusion about what role pharmaceutical companies play. What is the role of the so-called “Big Pharma” in medical progress?

Jonathan Ilicki: Big Pharma does play a crucial role. Working clinically, I experienced widespread skepticism toward pharmaceutical companies, often due to real misconduct in the past. But I think you have to put that into the context of all the tremendous benefits and utility that pharmaceutical companies have brought to humanity. Despite the valid criticisms, the process of bringing safe and effective treatments from concept to patient proves the industry's vital role in healthcare. While it's necessary to critique and hold these companies accountable, we must also appreciate the positive impact they've had on public health and medical science. And this impact is much bigger than isolated historical episodes of misconduct.

Philip Skogsberg: What's the biggest misconception about the healthcare system among the general public?

Jonathan Ilicki: A misconception I often hear is that healthcare is only reactive and not preventive. First of all, more can always be done to prevent illness. So it’s always true that healthcare can be more preventive, even in situations when the marginal benefit is negligible. It's also incorrect to say that prevention isn't a priority. An example that comes to mind is that during a period of about 25 years here in Sweden, we managed to reduce the mortality rate from heart attacks by half. In other words, the risk of dying from a heart attack was reduced by 50%. One potential explanation could be that we have gotten better at detecting milder heart attacks that went undetected before. If you identify a greater number of milder cases, then you reduce the mortality. But actually, we also managed to reduce the incidence of heart attacks. This progress shows that while the system can and should continue to improve its preventive measures, it has already made substantial strides in this direction. Recognizing the nuanced reality—that healthcare does focus on prevention but still has room for improvement—is crucial to understanding the system's complexities and challenges.

Philip Skogsberg: Speaking of Healthcare Systems, maybe we should talk a little bit about the differences between European or Scandinavian-style healthcare systems and the US; I think what is often referred to as a single-payer healthcare system versus one with “multiple payers,” private vs. public, etc. What role do private enterprise and entrepreneurship play in the single-payer/public healthcare system, specifically?

Jonathan Ilicki: So, in healthcare, we have a few different system archetypes. There's the Beveridge model, named after William Beveridge, where the government governs, pays for, and provides healthcare through taxation, with patients paying nothing or very little. Then there's the Bismarck model, characterized by non-profit insurance companies and a mix of public and private provision, funded by employer and employee contributions, such as in the Netherlands. We also have national health systems or single-payer models, where the government acts as the insurer, and both public and private entities can provide care funded mainly through taxation. Lastly, there's the out-of-pocket model, where whoever needs it pays directly for their healthcare.

In reality, countries often blend these models across several dimensions, influenced by ethical, moral, and economic perspectives. However, something I often see being overlooked in the discussion about which healthcare system is the best is the aspect of path dependency. Even if one model were hypothetically superior, transitioning from the existing system can be highly challenging due to entrenched practices and local factors; the “path” that has been taken. For instance, if we look at Sweden hypothetically, even if we knew for certain that transitioning to an out-of-pocket system would be better (which I don't believe), the challenge of deviating from the established path is significant. Healthcare reform is rarely drastic because altering entrenched systems is complex and influenced by numerous local factors. This means a model successful in one country might not be easily transferable to another, even if they appear similar.

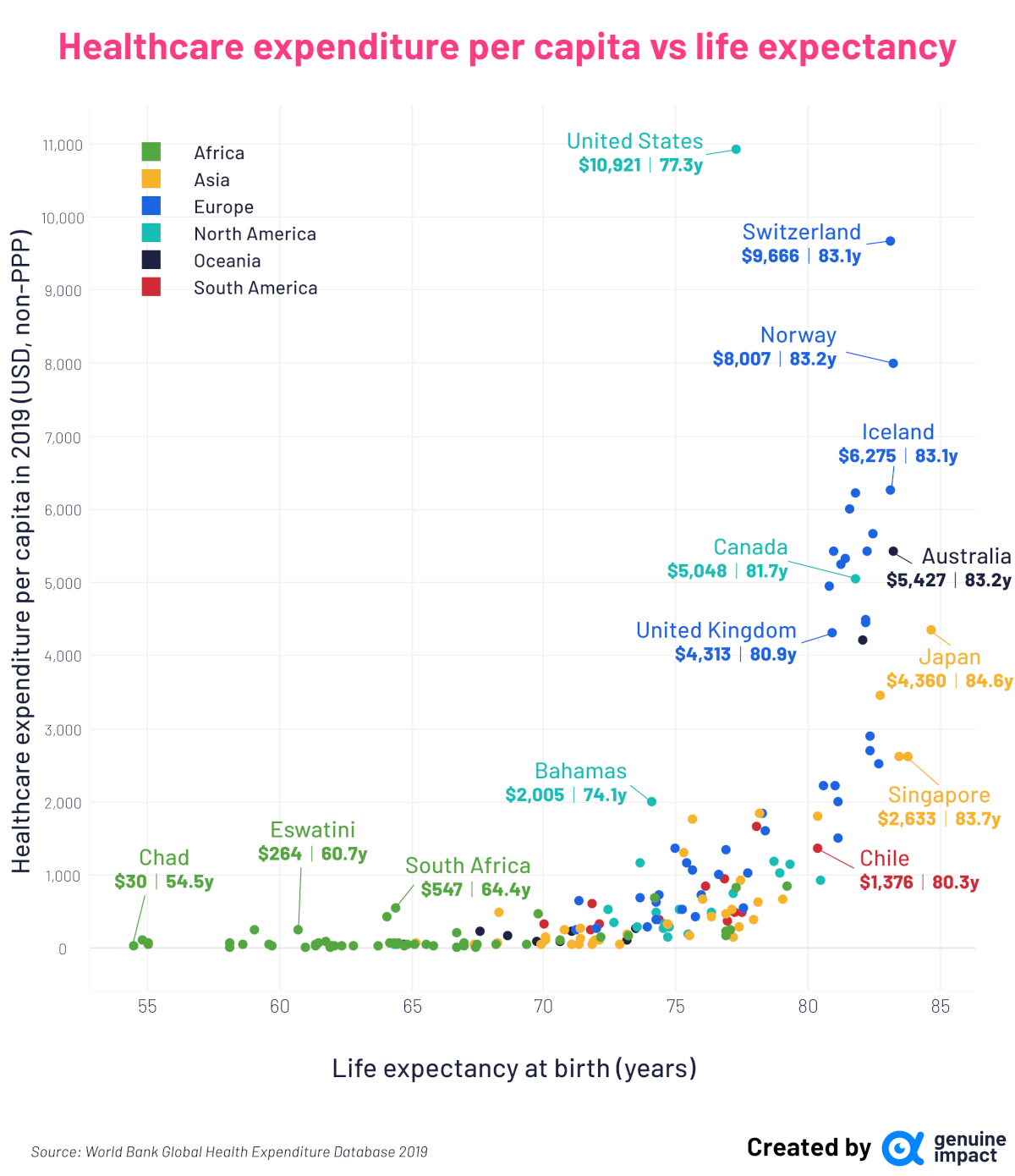

When it comes to the second part of the question on the role of private enterprise and entrepreneurship, the US plays a significant role in driving global innovation in healthcare. If you want to have large commercial success, you have to go to the US market. Innovations in healthcare, like new devices, new drugs, or new diagnostics, will often cost a lot to develop. So companies need to raise venture capital, and venture funds need to invest in things that can return a lot of money because they know most investments will fail. However, the downside is that if you compare the US overall healthcare expenditure with proxies for relevant outcomes, then the US is an outlier. The life expectancy isn’t great per dollar spent. However, that needs to be deaveraged, as the US is a fragmented country when it comes to healthcare access and equity. But, having said that, the US plays an oversized role in financing innovations that all of humanity and all countries get to take part in.

When it comes to single-payer systems like Sweden, for example, we have universal healthcare with both public and private provision, but where the vast majority is state-financed, with only a very small portion not financed by the state. This model is useful for thinking about risk; an important aspect of all healthcare provision is the transfer and management of risk. For instance, if you come to the emergency department with severe abdominal pain and vomiting, the physician assesses you, perhaps gives you medication, and advises you to go home and call if it gets worse. Most people trust the physician's judgment and follow their advice, and most often, they recover. This trust is based on a system designed to manage the risk associated with not knowing the exact nature of an illness and how to treat it effectively.

In many cases, the exact problem may not be clear, nor whether the prescribed treatment will guarantee improvement. This is where clinicians take on the responsibility of managing that risk based on their knowledge and the patient's specific situation. They might send a patient home, accepting the small risk that the condition could be some rare lethal condition that happens only 0.001% of the time. This balancing act between known and unknown factors is crucial in healthcare, especially in a single-payer system where the focus is on maximizing health outcomes for each dollar spent.

However, investing in innovation within such a system carries its own risks. Suppose a regional or national government decides to allocate, say, 5% of its budget to exploring new ways to deliver care more efficiently. While innovation is necessary, it inherently involves a high risk of failure [to deliver outcomes], particularly for significant innovations. So, in that way, deciding to fund innovation could be seen as a risky move, potentially wasting resources that could have been used more effectively elsewhere. Potentially risking many people’s lives. That’s why such systems tend to focus on low-risk improvements based on proven knowledge.

Here, I think private enterprises are better positioned to assume some of these innovation risks. They can invest additional resources with the hope of developing more efficient care delivery models. The most important thing is that when these ventures truly succeed, they not only benefit the private sector but will enhance the broader healthcare system as these innovations diffuse and improve health outcomes over time.

This goes back to your point about the role of pharma companies in healthcare. Critiques of the industry, particularly regarding the high cost of medications, often overlook the real long-term benefits of these innovations. So, while some treatments may be expensive in the short term, if you take the really long-term view, we know that the drugs’ patents eventually will run out. And then, for the rest of humanity's history, we will be able to produce these molecules at extremely cheap costs, which will benefit millions and billions of people. You need this long-view perspective to see the potential of this model to contribute significantly to global healthcare despite its imperfections.

Philip Skogsberg: Essentially, there's a theoretical finite number of useful combinations of molecules in the universe that can be applied to medicine to enhance human outcomes. It’s a bit like mining for gold in that there’s a finite amount of gold on earth. Eventually, we might reach an asymptote in our ability to find more useful combinations, leading us to a state of extreme abundance in the availability of medicines or medical knowledge.

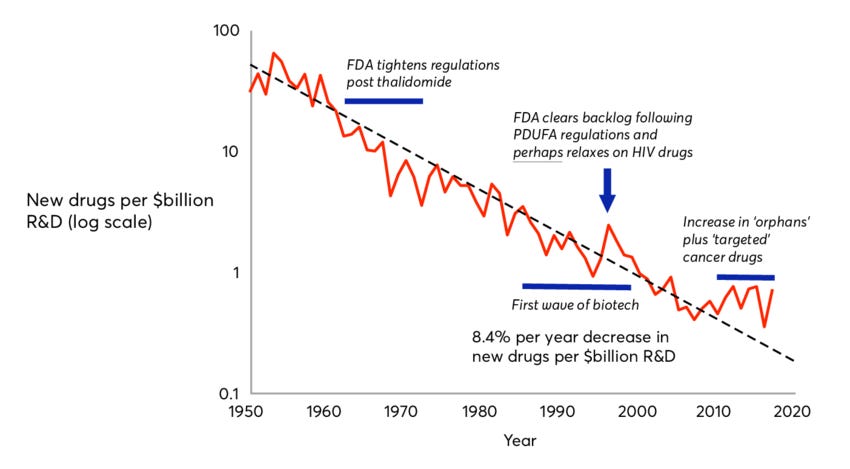

Jonathan Ilicki: There are a couple of points to consider here. First, there's something known as Eroom's law, essentially Moore's Law in reverse, which suggests that the cost of developing a new drug doubles approximately every nine years. This indicates we might be reaching a point where most easy discoveries have been made, and developing new blockbuster drugs is becoming increasingly challenging. On the other hand, we're entering an exciting era where artificial intelligence, even before the surge in Large Language Models, is being leveraged to enhance the drug development process. AI helps us identify more promising "gold mines" for exploration.

Additionally, the boundaries of healthcare are malleable. The scope of what we aim to treat or prevent is ever-expanding. For example, if we decide to focus more on prevention, we start to identify and address precursors to diseases, such as treating hypertension to prevent heart attacks. This ongoing expansion of healthcare's scope suggests it will be a long time before we exhaust all avenues for solving health problems. As we focus more and more on preventive measures, we redefine medical conditions and their precursors, continuously broadening the horizon of the healthcare challenges to be addressed.

Philip Skogsberg: What do you think are the primary drivers of the increasing costs in healthcare? It seems that healthcare costs have been steadily increasing over the past century in any system, whether private or public.

Jonathan Ilicki: There are various explanations for the rising costs, ranging from Baumol's cost disease to other factors. However, one perspective I find most convincing is that healthcare has become more expensive precisely because it has been successful. Over generations, we've accumulated a vast amount of medical knowledge, enabling treatments that were once considered science fiction. Now, we're treating rare genetic diseases that were previously death sentences, and as healthcare succeeds, people live longer, often with chronic conditions, which inevitably drives up costs.

So, in a way, the more successful we are in extending life and improving health, the more costs will rise. This is actually an optimistic take because it reflects our achievements in healthcare. But we want to succeed in terms of increasing both lifespan and health span - in other words, the period of time when an individual retains their health and independence. But it gets tricky when we increase one much more than the other. Similarly, if we focus on advancements that improve the quality of care without equally addressing efficiency, it creates a very large gap, which, in turn, creates an incredible strain on health care. I believe that AI has high potential to decrease that gap; the gap between the progress on quality improvements and efficiency improvements.

Philip Skogsberg: First, how so?

Jonathan Ilicki: Healthcare is extremely heterogeneous. There's a wide array of specialties, processes, and settings, making it as complex and varied as a painting with a million different colors. In most of these settings, there’s the basic application of general knowledge—clinicians use guidelines or textbook information to address specific patient situations. This involves not just the application of knowledge but also the communication of it between clinician and patient and the coordination of this knowledge, often facilitated by an electronic health record [EHR]. Ensuring subsequent clinicians are aware of a patient's history necessitates detailed documentation. All of these things are key activities that just must get done.

With patients now living longer, often with chronic conditions, and having more frequent interactions with healthcare, the frequency of these key activities also increases. Addressing this growing demand requires solutions that can alleviate the workload and address these points. This is where the potential of AI and Large Language Models comes into play, particularly in applying general knowledge to specific cases.

Large language models have demonstrated the ability to correctly answer 90% of medical exam questions. This doesn't mean they can replace clinicians who perform a multitude of tasks, but it suggests they can significantly aid in recalling and providing relevant data. This enhancement could improve the point of care by ensuring the most important information is utilized in clinical settings, thereby saving time and improving efficiency.

However, while Large Language Models can augment many aspects of healthcare, they cannot replace all human interactions, especially those that involve complex, nuanced communication. Where they can make a substantial difference is in standardizing certain interactions and in documentation. The healthcare sector's increasing specialization demands more documentation to ensure seamless coordination across different specialties. As healthcare evolves, the demand for quality necessitates even more comprehensive documentation to track improvements and understand patient outcomes.

In this context, something as straightforward as the automatic transcription of conversations could significantly enhance healthcare efficiency by reducing something as unsexy as the time clinicians spend on administrative tasks, allowing them to dedicate more time to patient care. This optimistic view on the role of AI in healthcare underlines its potential to improve efficiency significantly, though not necessarily the quality of care, by automating and streamlining routine tasks and documentation processes.

Philip Skogsberg: That’s very exciting, but it also strikes me that this probably won't ever decrease the costs of healthcare. If anything, it'll keep increasing the costs, which may actually not be that bad because, overall, society is getting richer. So it's more a matter of how much money we want to spend on it. One of the reasons healthcare costs keep increasing, setting aside specific things like Baumol’s cost disease, is that there's basically an infinite demand for more healthcare.

Jonathan Ilicki: That’s an insightful point. If we just look at the history of healthcare, because we can define new conditions as being something healthcare should treat, and because we raise our bar continuously on what we demand from our everyday life, the demand really is infinite.

I think that cost reduction is more a political question than a technological question, it’s a question of priorities with other societal functions. I recall the first time working as a physician in a hospital, we had these paper charts of patient information tucked away in an archive. It was terrible because when a patient was really sick and came to the emergency room, I had no information at hand. But then, when the hospital digitized and moved it onto a computer screen, all the information was there, but it was designed as a stack of papers, so you had to click through lots of pages to find what you were looking for; you couldn't search for text.

For example, there are studies from the US that when they introduced EHRs, the quality went up, adverse events and mistakes were reduced, but the efficiency also went down. So, not all technologies save time, but when technologies do save time, usually, the first 15 or 20 percent or so of the saved time is taken by the clinical staff. They now have time to go and pee between patient meetings, or they have time to have a 30-minute lunch. So, even if it doesn't reduce costs, I still think it has a meaningful impact on the clinicians' workplace and their work environment.

Philip Skogsberg: On the topic of AI and humans versus machines, what will be the role of human clinicians several decades from now when so much more has been automated? You can imagine a world where diagnostics are done with excellent accuracy by AIs and where robotics has advanced to the point that no human surgeon ever operates on patients. What role do humans have in that system?

Jonathan Ilicki: That's a really good question. I think there will be a lot of activities where we'll still need human interaction for several reasons. Clinicians will be needed both for interpersonal interaction – I think it'll take time before we can accept a cancer diagnosis from an automated robot – and also to carry risk. Some conditions are extremely standardized, like a urinary tract infection in a young woman with an uncomplicated case. It's very algorithmic how you diagnose and treat it. Straightforward conditions like that might be automated because they're very safe to automate, and you can create rules to catch them. But once you start shifting to more complex things, there are so many subjective assessments that I don't think we'll be able to shift entirely to an automated system.

If someone comes to the ED with chest pain, you can do different tests, and they can either be very conclusive or sometimes find things in the middle. The better we become at understanding things, the more nuances we'll see. And there are so many gray zones, and that's just one dimension. There are so many small subjective assessments to make that I find it unlikely we'll be able to automate away the human from all those interactions.

And there's also a third aspect: a model for conceptualizing care processes. We have sequential processes for conditions and treatments we understand well, following a clear flowchart. However, for less understood aspects, care becomes iterative, involving a series of tests and trial-and-error approaches. This iterative care process, necessitated by the vast number of biological permutations and variations, remains a crucial part of healthcare. As we standardize treatment for common conditions, more resources can be allocated to these iterative, rare cases. Therefore, the need for human intervention persists across these dimensions even as we continue to push the frontiers of healthcare further and further out.

Philip Skogsberg: I wonder if this changes if we look far enough ahead into the future. Assuming AI and related technologies continue advancing without major limits, we could reach a point where AI can do almost everything better than humans. The role of human clinicians and nurses might then mostly revolve around the preference for human interaction over machines. It's conceivable that AI could outperform humans in diagnostics, which you hinted at. But there will still be a need for human care and empathy in healthcare.

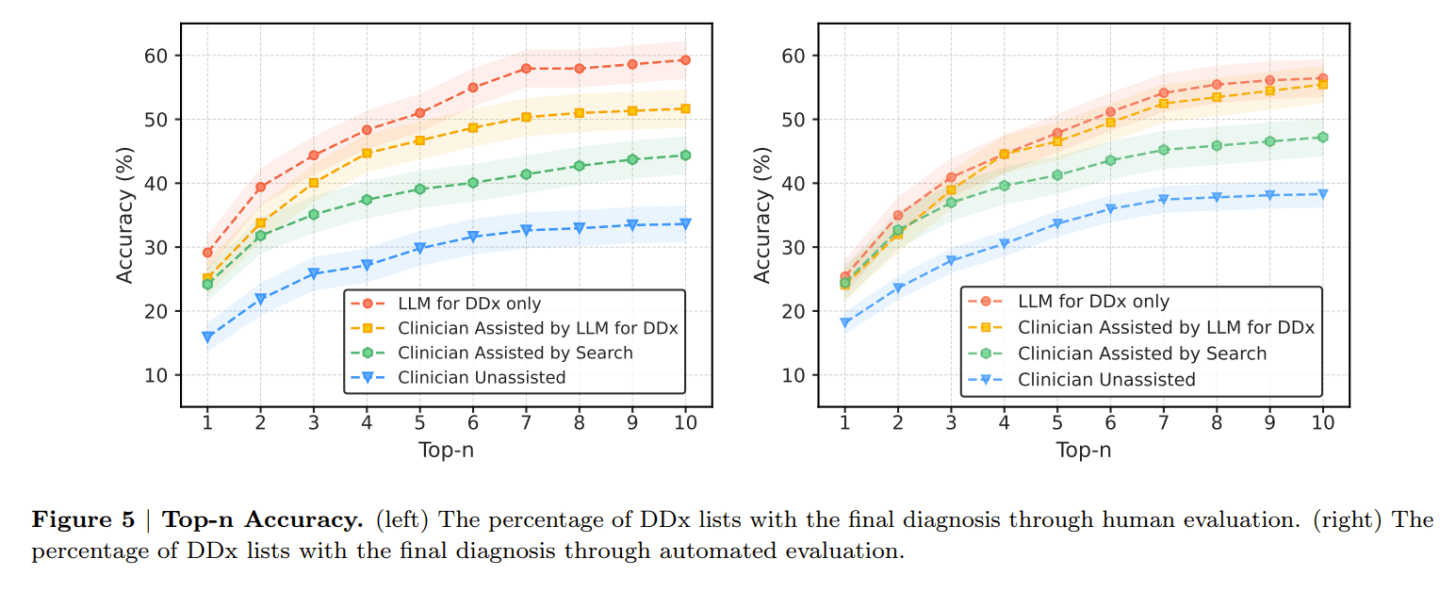

Jonathan Ilicki: We’re already there, I recall a study that came out recently that showed LLMs outperformed GP doctors’ diagnostic accuracy by creating more comprehensive differential diagnoses lists. However, I think our differing views hinge on two main points: the speed of progress (the horizon) and the ultimate limits (the asymptote) of AI in healthcare.

We've seen incredible science fiction-like progress in the past years when it comes to LLMs in healthcare. So I think that's beyond the debate, but I'm not sure that it will all be smooth sailing and exponential improvements in accuracy and performance without any obstacles.

The reason is that there are all these things that you can't really capture data about in an efficient way yet. And it’s also about who carries the risk; if you're creating, let's say, AI software for healthcare, there are many regulatory demands you have to meet. You have to show that the software performs according to specific standards and is consistent in its output because otherwise, you won’t get the regulatory approval, and then you can't sell it to healthcare providers. It’s very difficult for a manufacturer to guarantee error-free performance for some of these tasks because the permutations [with LLMs] are endless, and the risk is so high. And there's no healthcare provider who'd want to use a system that doesn't have these guarantees in place because they need to rely on the software’s accuracy themselves. This is the very boring medical, legal, and regulatory aspect, but it’s the kind of thing that slows or limits the ability of AI or just software in general to impact healthcare.

Philip Skogsberg: Trust is a crucial factor, too. While recent AI advancements are really impressive, the unpredictability of so-called 'hallucinations' by LLMs introduces a level of uncertainty. We're comfortable with the risks of a doctor making a faulty diagnosis. That is an error that's priced into the system because it's a human doing it; it’s familiar. But we won’t accept that if it's a machine making the same error. I think this is also why self-driving cars aren't a big thing yet, even though they're better than humans in most circumstances. We don’t accept the same level of error or risk with machines as we can with humans.

Jonathan Ilicki: Absolutely, this is a critical point. It's evident that simply matching human performance isn't sufficient for these AI systems. The real challenge lies in determining how much better an AI must be at diagnosing to be considered reliable, especially when humans are prone to errors. If a robot, armed with the collective knowledge of the best physicians, outperforms them in accuracy, the question then becomes about the societal threshold for acceptance. How much more accurate must the AI be to overcome the occasional, unpredictable hallucination it might make? This, I believe, boils down to societal norms and their evolution, which I anticipate might shift, though it may take many years.

Philip Skogsberg: What other sorts of topics or problems are you particularly interested in right now?

Jonathan Ilicki: I feel fortunate that I early on reflected on the system flaws I saw in my clinical work, which led me on a path of learning and improving healthcare in other ways. Now, as I’ve started working with investing and venture capital, I'm encountering new perspectives and challenges I hadn’t considered much before. I'm currently intrigued by the dynamics of how ideas gain traction and capital. Why do certain ideas, companies, or innovations succeed while others don't? I'm trying to maintain a naive perspective for as long as possible to discern if there are underlying issues within the [venture] model itself that warrant addressing somehow. This includes understanding decision-making processes in venture capital and beyond. Maybe a topic for a future discussion!

Philip Skogsberg: Final question then: what are one or two books that you would recommend? Books that have stayed with you for a long time.

Jonathan Ilicki: A good non-healthcare book is "This Idea is Brilliant". It’s a collection of short essays by a diverse group of thinkers on scientific ideas they believe everyone should know about. It's intellectually stimulating, offering insights across a broad range of subjects in an accessible format. A controversial and convincing healthcare book is "Medical Nihilism" by Jacob Stegenga, where he argues that many medical interventions may not be as effective as we think, advocating for a more measured approach to new treatments. It's a provocative read that encourages critical thinking about the impact and limitations of modern medicine, promoting a philosophy of "gentle medicine."

Share this post