Why Europe Doesn't Innovate

Europe has been playing defense for so long that it forgot how to innovate.

Introduction

As a millennial growing up in Sweden during the 90s and 2000s, I remember being surrounded by European tech products, like mobile phones from Ericsson, Nokia, and Siemens. Today, no major consumer tech products are made by European companies.

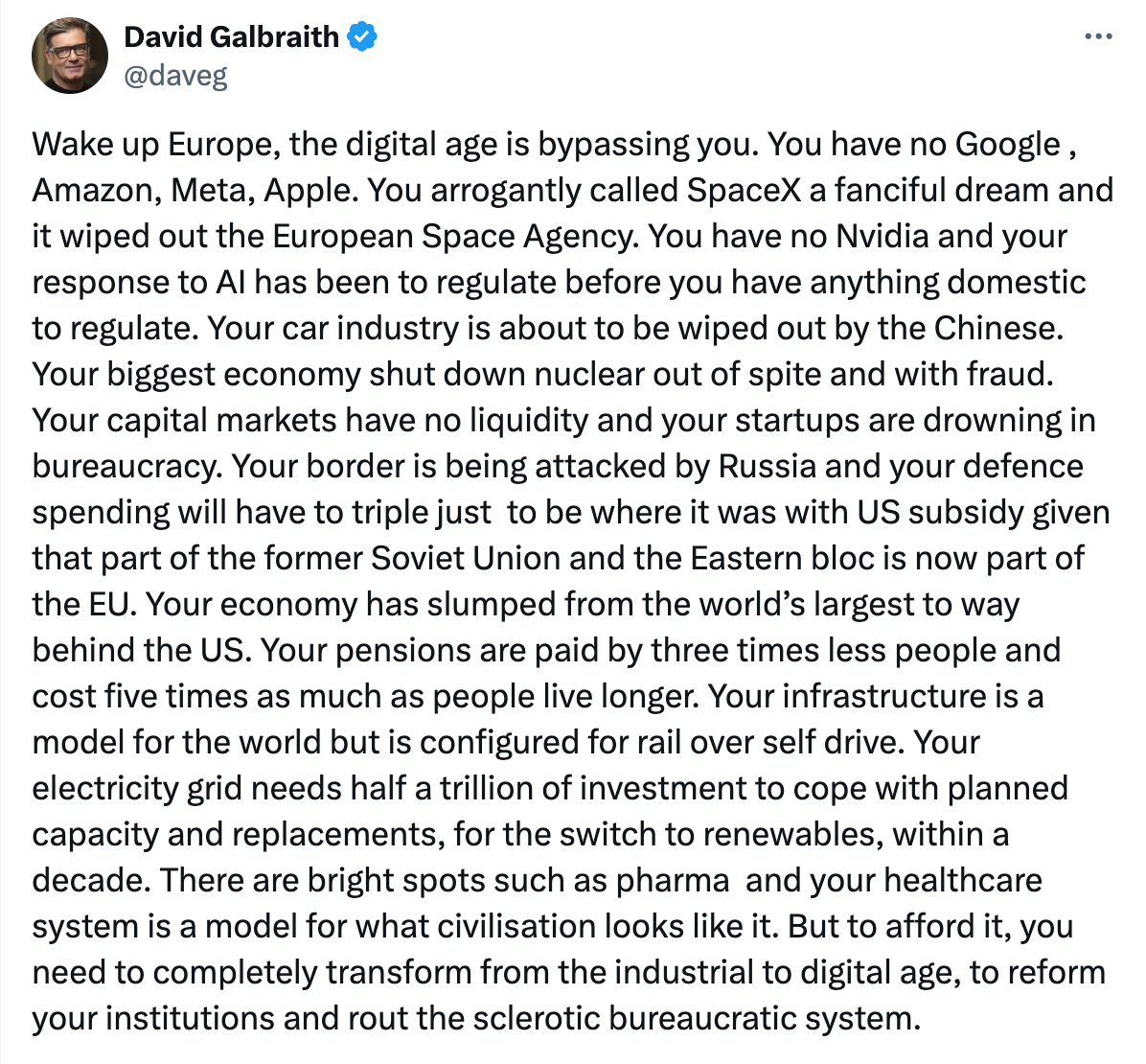

Europe has a long legacy as the bedrock of innovation and economic growth, going back to the Industrial Revolution and beyond. Yet, it has now been falling behind for many decades. It has been harvesting the fruits of its labor from centuries past but has all but forgotten to sow new seeds for the future. More and more voices have been raised that are growing increasingly frustrated with what is seen as Europe’s squandered potential:

The picture of innovation and technological progress in Europe is mixed, but its lack of innovative prowess compared to the US and China is becoming more and more apparent:

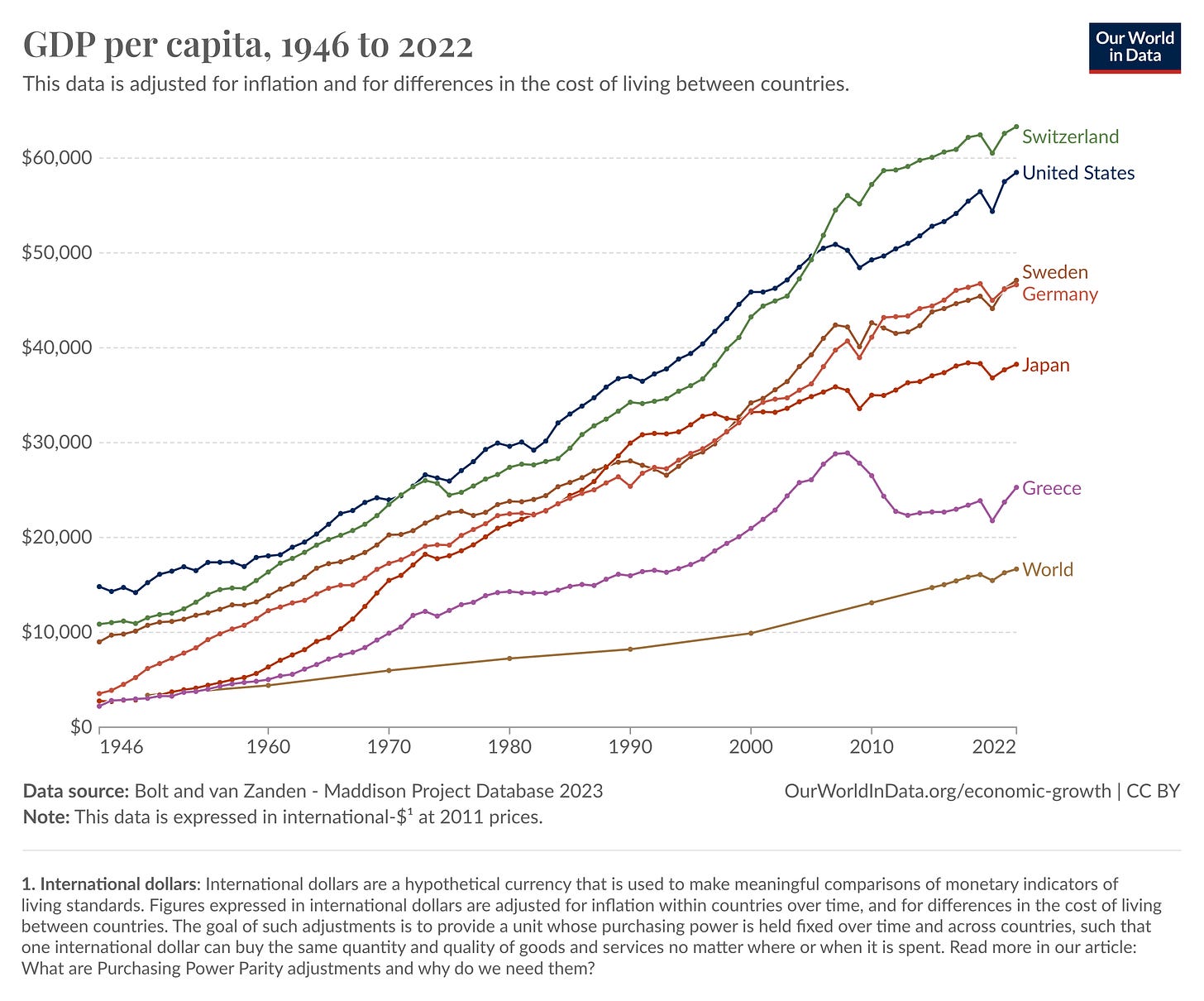

Stagnating economic growth across the EU block. The biggest economies in the EU (and Europe more broadly), like France, Germany and Italy, have all been growing slowly or stagnating over the last ~2 decades. The average annual GDP growth in the EU has been around 1.3%; in the euro area, it has been around 1.1% (1.8% in the US).1 Sweden - one of the wealthier European countries - is still lagging behind the US in productivity growth and GDP per Capita. Even the poorer US states today have a higher GDP per capita relative to many bigger EU economies. For example, Italy is just ahead of Mississipi.

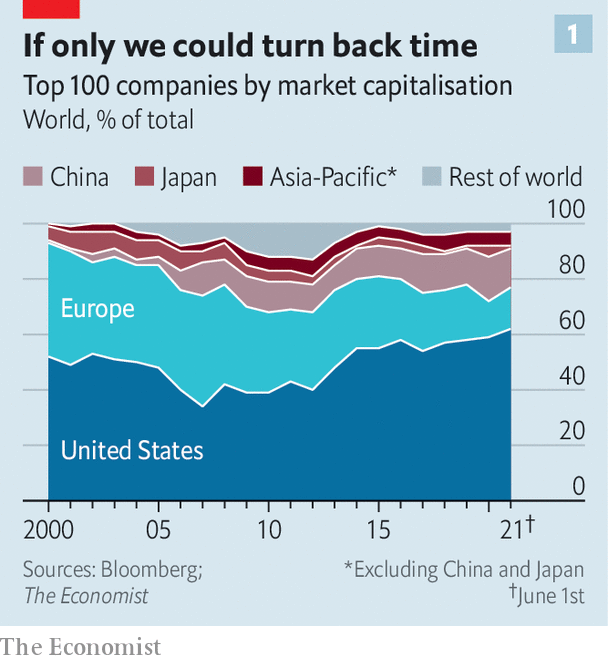

No Euro-native Big Tech anymore. While Europe still has a lot of software application companies, it doesn’t have any of its own ultra-big infrastructure or platform companies like Google, Meta, or Apple. The biggest companies in the world today are mostly from the US and some from China. Europe’s most prominent companies in terms of market cap are from “traditional” industries like healthcare (Novo Nordisk), transportation (VW), and fashion (LVMH). In tech, the biggest companies, like SAP and ASML, don’t even come close to the size of just one or two of the biggest American companies.

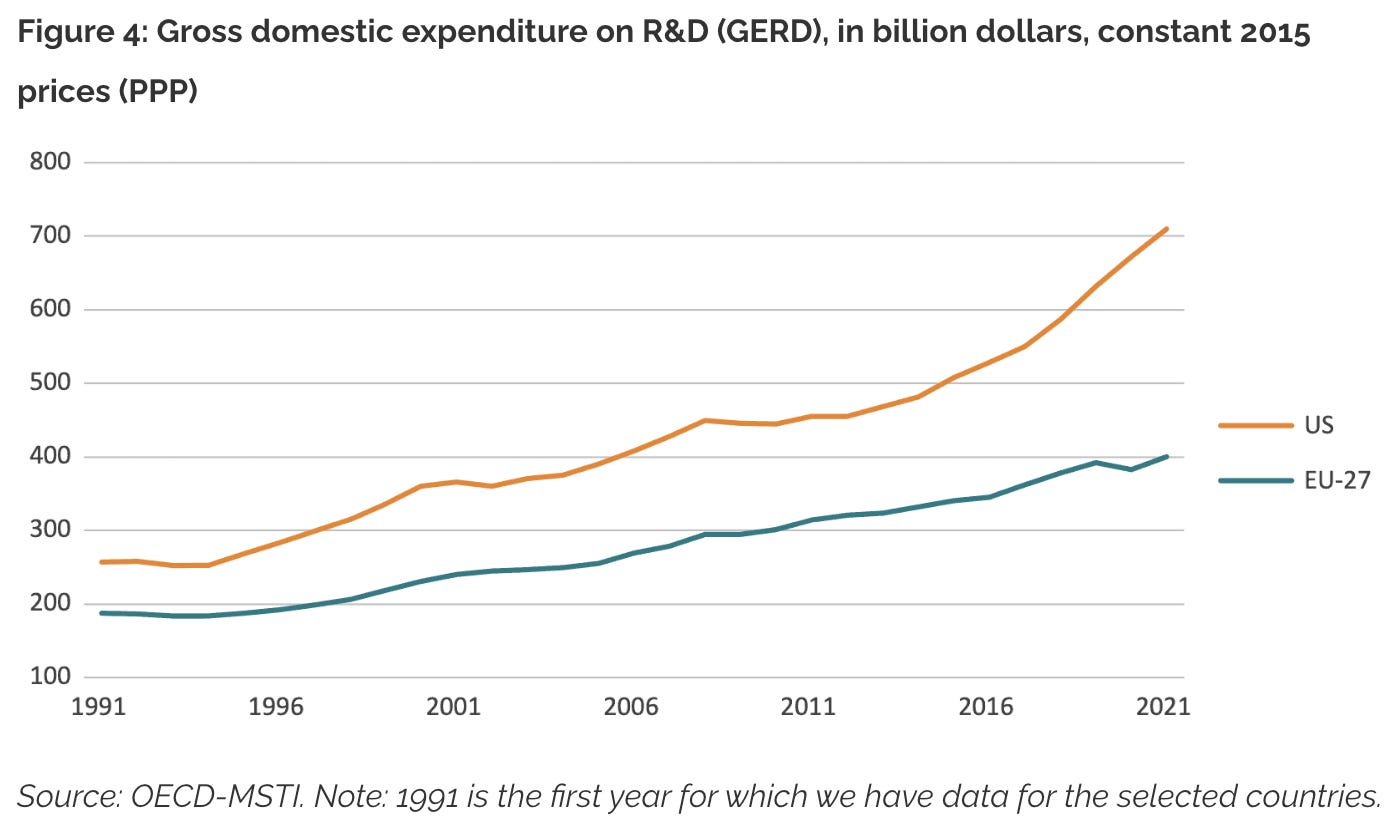

Falling behind on innovation. In the past half-century or so, few world-changing technology paradigms or products have come from European companies. The Internet, smartphones, blockchains, and AI have all emerged elsewhere (mainly in the US). Europe is home to many of the best universities in the world, such as Oxford, Cambridge, ETH Zurich, KTH in Stockholm, the Institute of Lausanne, and more. They also produce many of the world’s most talented scientists and engineers. Yet, many end up moving to the US because American universities and companies are generally more well-funded. In 2021, the US spent around ~$700B in R&D compared to the EU’s ~$400, a 75% gap.

Why Europe isn’t innovating

With the amount of online commentary about a stagnating Europe, one might come away thinking that it has become a technological and economic backwater. This is obviously not true; Europe is still one of the most modern and best places to live. Still, many feel (as I certainly do) that it should and can do better.

So, why is Europe stagnating and not innovating anymore? Where are all the Euro-based Unicorns? Several explanations have been proposed:

Lack of capital for startups and scaleups. The US and East Asia have more robust private investment ecosystems, and startups have access to more capital. In particular, a late-stage funding gap for scaleups makes it harder for them to grow as fast as their US peers.

Employee protections. In European countries, it’s generally harder for employers to fire employees, which is good for individuals but often bad for companies’ (especially startups) competitiveness and financial agility.

Employee compensation. In the EU, a startup employee's ability to easily get compensated with stock options is more complicated and highly taxed than in the US.

Regulatory barriers and higher taxes. The EU has a higher regulatory density, tax rates, and a more heavy-handed government policy than the US.

Lack of a large, unified market. Despite the EU's single market and geographic proximity, the European market is fragmented with many different national bureaucratic processes and legal frameworks.

Lower R&D spend and innovation. While there are national and EU-wide innovation initiatives like Horizon Europe, the EU spends considerably less on R&D as a share of GDP compared to the US.

Risk-averse and “lazy” working culture. The perception is that Europeans are generally more risk-averse or less entrepreneurial and prefer more leisure time to making money.

Culture

As you can probably surmise, many of these proposed causes are related. Lower R&D funding and investment capital are likely due to the fragmented European market, regulations, taxes, and a more risk-averse investment culture, among other things.

In the US, investors expect startups to take “big swings,” grow fast, and forgo making money until much later on. European investors have generally preferred to make “safer bets” and invest in startups that are already generating revenue or are profitable.

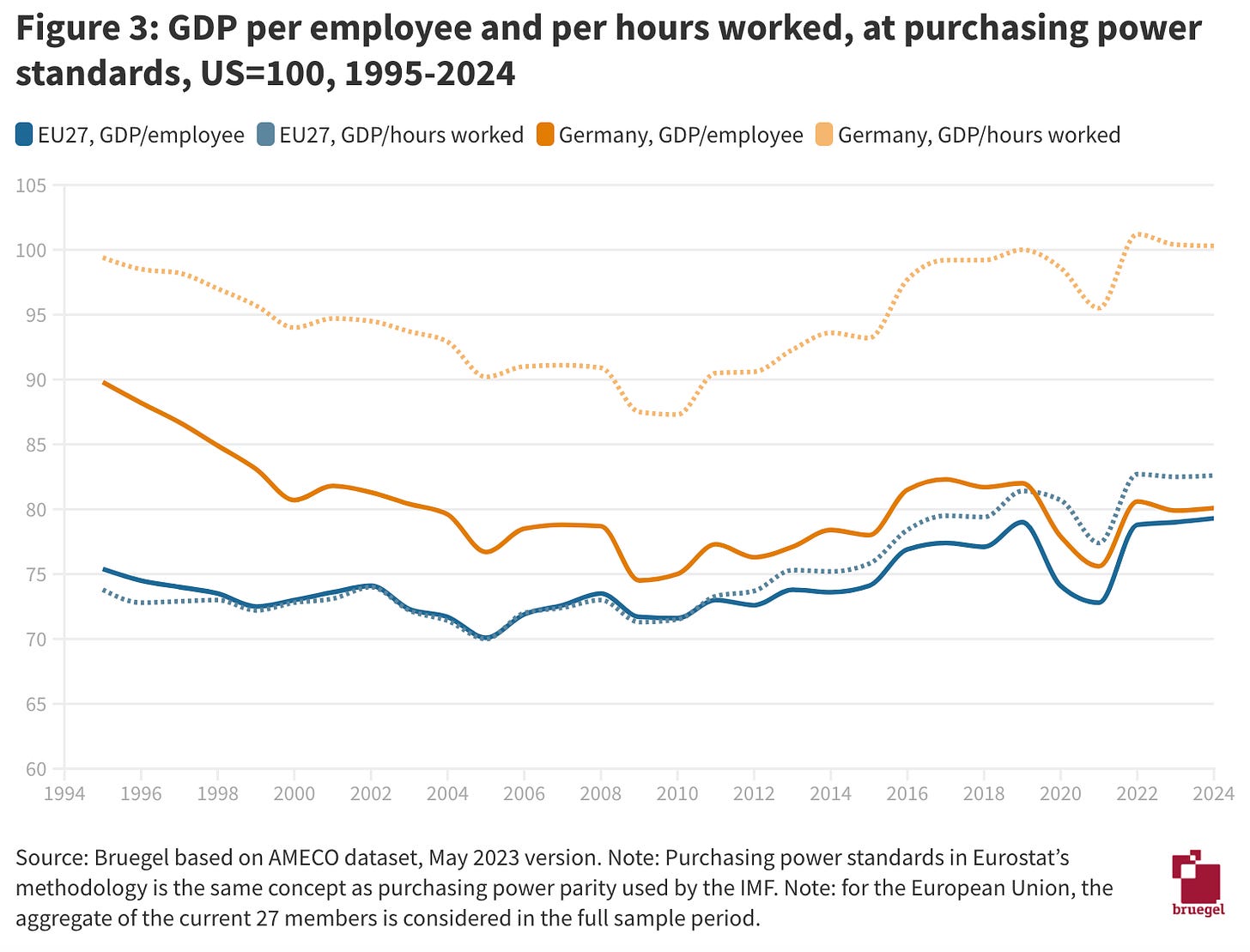

While this different kind of mindset goes some way to explaining the lower amounts of capital, I find the cultural explanations lacking. Europeans do seem to value leisure time more and work fewer hours (largely because they have more holidays and do more part-time work), but this differs per country. Contrary to a widely held perception, Greeks work the most hours annually in Europe. And several countries are actually about as productive per hour worked as Americans when adjusting for purchasing power (PPP). Although the average is lower, the GDP per hour worked is similar or even higher in Western/Northern European nations like Germany, Luxembourg, Belgium, and Denmark than in the U.S.

Despite this more nuanced view of European productivity, it’s an inescapable fact that the US has been pulling ahead overall. But I don’t think this is primarily a matter of Europeans being lazier. When it comes to innovation and new technology, statistics about the average worker don’t give us the full picture. Entrepreneurs, scientists, and business leaders - those at the forefront of innovation - aren’t average people, and I suspect they work as hard regardless of their origins.

The bigger problem for Europe is the legal, bureaucratic, and linguistic fragmentation of the European market(s). There are deeper structural issues at play.

A fragmented market

A US startup that wants to expand has a market of 340 million people under a common legal and regulatory environment, sharing the same language, payment methods, and cultural expectations, etc. There’s also ample access to venture capital to bring new products and ideas to market and scale them quickly despite the financial risks.

Moreover, most US startups are incorporated as a Delaware corporation, the standard for tech startups. This makes it straightforward for investors to fund companies from anywhere in the US. The abundance of capital itself is also due to the large domestic market available for US-native startups.

This isn't the reality for European startups. Despite the EU's single internal market for goods and services and the ability to move freely within the Schengen area, startups can't scale as easily as their US counterparts.

In the EU, there are 27 different legal frameworks, tax systems, languages, and education systems, as well as stark cultural differences. This makes it much less straightforward to grow quickly, reducing the EU consumer market of ~450 million to smaller national or regional ones. Since every country has its own legal corporate entity for companies, it’s harder for international investors to fund companies from Europe, restricting capital from US investors. Although some countries in Europe have very business-friendly laws and corporate environments, too many, like Italy and France, have frequently topped the rankings of the most complex and least startup-friendly nations.

While goods can move freely within the EU thanks to the so-called Single Market, this isn't the case for most services. With services (digital or otherwise) making up 70%+ of the European economy, it represents an untapped opportunity for the EU to enhance trade and economic growth. Despite previous attempts2 to improve the flow of services within the EU, regulatory differences across the continent make it hard, if not impossible, for many companies within service-oriented sectors to expand outside their national market. For example, professional qualifications aren't uniformly recognized across the EU, and in sectors like healthcare, finance, and law, companies are mostly restricted to operating nationally.

All this contributes to a fragmented and less competitive market. The average European firm is smaller than its US counterpart because the fragmented nature of the European market makes it harder for firms to grow as big. Small firms are typically slower at digitalization, and smaller markets create less competition, which contributes to firms that aren’t as well-run as they could be. This, in turn, leads to less productive firms overall and less economic growth.

There’s no “Big Tech” in Europe

In 2000, the EU initiated the Lisbon strategy to transform its economy into a full “knowledge-based economy” by prioritizing innovation, R&D, and a more skilled workforce while aiming for 3% of GDP in R&D. However, its implementation was patchy across member states, and Europe failed to fully capitalize on the dot-com boom and early Internet-era technology as the US did. European tech companies fell behind and were eventually overtaken by American companies like Google, Meta, Apple, and Amazon. Despite the public’s growing distrust of “big tech,” these companies make up a disproportionate share of the market value and have had many positive downstream effects on the tech ecosystem and the economy.

In addition, the EU has been forceful in limiting natural monopolies and preventing big company mergers, like Siemens' proposed acquisition of rail and transportation company Alstom in 2019, to avoid inhibiting competition. The absence of large European tech companies decreases its innovation prowess in emerging industries like AI. It also limits exit opportunities for European founders, as large American companies often buy successful startups and scaleups, draining capital and talent from Europe.

Lacking its own big tech, the EU has instead leveraged its large, relatively rich consumer market to push regulations targeting these technologies and companies. The EU launched the privacy regulation GDPR in 2018 and has recently introduced an “ambitious” AI regulatory framework. This European approach was aptly captured in a Tweet by Lillian Li a few years ago:

Declining civilian and military industrial capacity

Although the United States military-industrial complex is often blamed for all kinds of problems in the world, it plays a significant role in driving downstream innovation. For one, governments can be big customers to companies that develop risky new technology, especially military tech. While some European countries like Sweden still have their own military industry,3 they’re not close to rivaling the US or China.

Most EU countries buy a lot of their weapons from the US, which gives the US money to invest in further military and defense research and innovation. Some of this makes its way into civil society through the diffusion of innovation and talent. For example, many cornerstone technologies, like the Internet, jet engines, and GPS, were developed by or as a result of the defense industry.

Moreover, the declining industrial capacity in the EU has significantly impacted innovation and competition, leading to reliance on imports for critical goods and in-demand products. This makes Europe vulnerable to global market fluctuations and conflict. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, and increasing tensions with China, it seems Europe has finally woken up to this lack of industrial capacity. It’s not just its defense industry but also areas like energy, climate tech, and semiconductors, to name a few, all of which are crucial for economic strength and prosperity (including security) in a world of increasing geopolitical tension.

Demographic changes and decreasing fertility

Over the long term, broad-based progress is a result of economic growth, which is, in turn, driven partly by population growth. Fertility rates have fallen across all developed and middle-income countries, and population growth is slowing everywhere outside of Sub-Saharan Africa and a few other places.

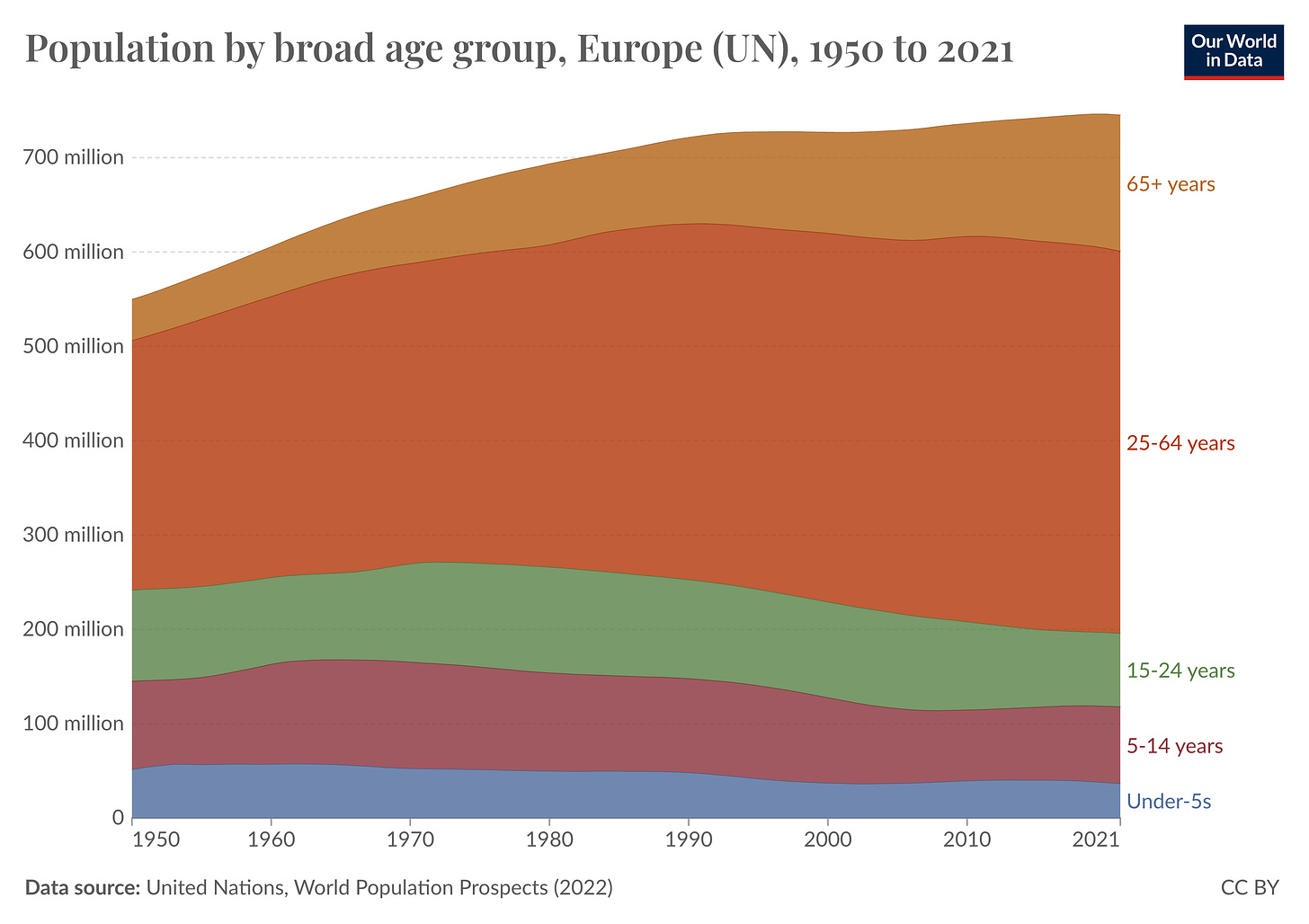

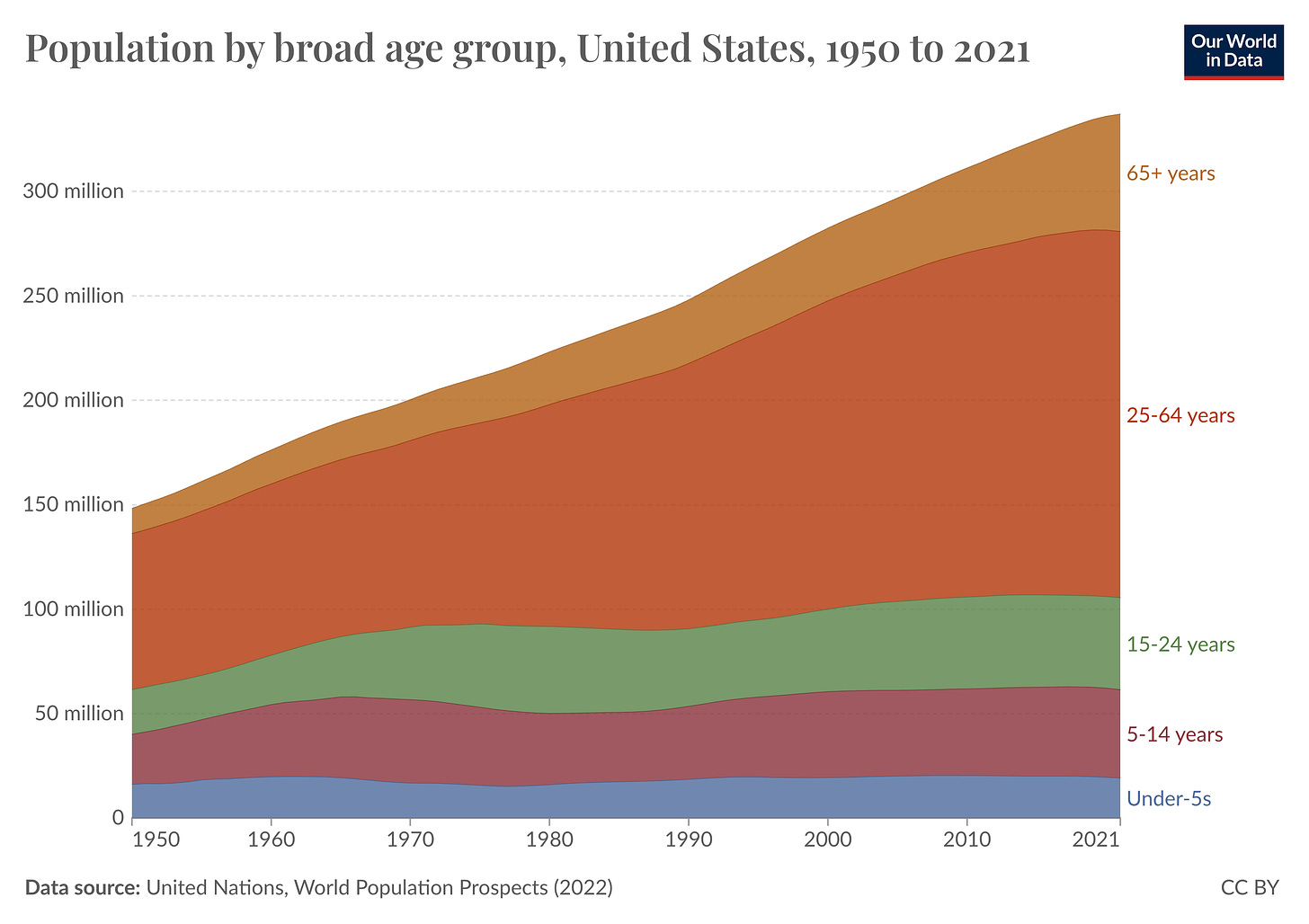

Most European countries have lower fertility rates than the United States, but the difference isn’t large (about 1.5 vs 1.7 children per woman in 2022 respectively). Nevertheless, Europe has been aging faster due to its earlier population growth rate slow-down. The working-age population has been stagnating or declining for decades. Youth unemployment has been higher, especially in Southern Europe. This has probably contributed to slower adoption and dissemination of new ideas, which are one of the key inputs to growth.

In contrast, the US population has continued to grow partly due to immigration. The US’ ability to attract and integrate immigrants has always been a major strength and contributor to its growth. Most European countries have not been as good at that. In fact, many CEOs or founders of the biggest American companies today are foreign-born; Sundar Pichai is the CEO of Google, and Satya Nadella is the CEO of Microsoft - both from India. Elon Musk of Tesla and SpaceX is from South Africa, among many others.

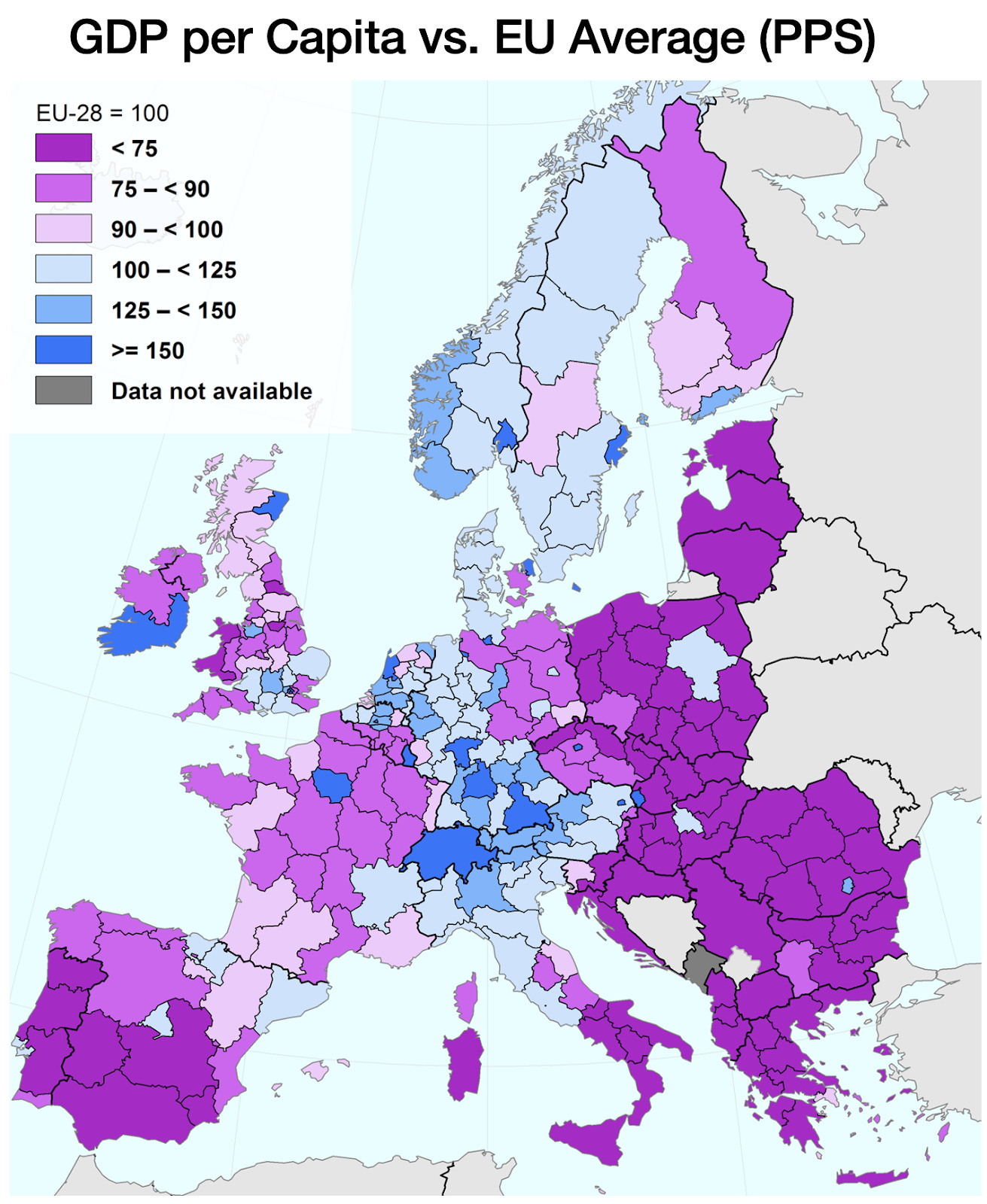

High-level data obscures details

In Europe, the Northern and some Western countries (and cities) have significantly higher GDP per capita compared to the average. As I noted above, many European countries or regions perform about as well as or better than the US, depending on what metric you’re looking at.

Likewise, the US is far from homogenous, with significant differences between rich states like California, New York, and Texas and states like Mississippi and Arkansas. Notably, one area that really stands out when it comes to driving growth and innovation is Silicon Valley. Its prominence is the result of a powerful agglomeration of talent, money (both private and public), and ideas that, taken together, have produced a disproportionally large amount of the world’s most valuable companies. If it were a country, it would be one of the richest. Although several cities in Europe, like Berlin, Paris, and Stockholm, have become prominent “tech hubs,” it lacks its own Silicon Valley. I think this is a major contributing factor to the wealth and prominence of the US in economic and technological comparisons.

Although GDP is an important and useful metric, it doesn’t capture everything we care about. It also obscures details like hours worked, purchasing power, and relative wealth. Marko Jukic, a writer for Palladium Magazine, argues that both Europe and the US are more alike in terms of wealth - and poverty - than many high-level metrics suggest:

In addition to adjusting for purchasing power and disposable income, an easy way to get closer to a real comparison of affluence is to adjust for hours worked, which lets you guess at leisure time, one of the most obviously desirable forms of wealth. According to The Economist, when adjusting for purchasing power and hours worked in 2022, the two most affluent countries by far are Norway and Luxembourg. Once you add in Denmark, Belgium, Switzerland, Austria, and Sweden—all the other countries ranked higher than the U.S.—you are no longer talking about one or two small and unrepresentative rich countries, but 52 million Europeans who are more affluent than the U.S. average. Perhaps we should think of these countries, collectively, as “Europe’s California,” rather than a few irrelevant and unrelated Vermonts. In any case, the 83 million Germans are at 97% of the U.S. figure, while the 68 million French are at 93% of it. Another chart, measuring net household disposable income in 2021 adjusted for actual individual consumption, purchasing power parity, and hours worked, found that Germany was the highest at 87% of the U.S. figure, followed by France at 85%, and Belgium at 85%.

Europeans value other things

Since most European countries are pretty well-functioning democracies, the policies of the EU will necessarily reflect the will of its people, at least to some extent. As a result, the EU focuses a lot on “popular” issues like consumer protection, immigration restriction, and climate policy rather than on policies that really promote technology and innovation. Europeans enjoy longer paid vacations, better employee protection, universal healthcare, lower income inequality, lower crime rates, and better consumer protection compared to the US and most other places. It might just be that Europeans prefer these things over being richer.

Why isn’t it enough for Europe to be a little less rich than the US when the average European has a comfortable lifestyle and works less? The problem is that we can’t take our wealth for granted. As I’ve argued at length, a growing economy is crucial to growing our material and social well-being and maintaining it in the first place, as a declining economy will eventually lead to zero-sum competition for a limited set of resources.

What should the EU do?

Government policies often do more harm than good despite the best of intentions. Yet good governance facilitates structure for growth and innovation - both nationally and internationally. The EU and its predecessor organizations were created in part to facilitate more seamless pan-European trade and economic growth. While some feel it has gone too far and is intruding on national sovereignty, it has arguably not gone far enough in establishing a robust framework for innovation and growth across Europe.

Over the years, many initiatives and changes have been proposed or implemented4, most notably the Euro. However, there are still many areas the EU, its member states, and its people should focus on to promote and facilitate innovation, growth, and prosperity.

Reducing market fragmentation

Although the EU has worked to enhance integration and minimize fragmentation over the years, such as through the Digital Single Market policy objective, subsequent legislative efforts have not made significant progress or have focused on the wrong areas. Rather than emphasizing growth-enhancing, unifying policies and legislations, the Digital Markets Act and Digital Services Act have, in practice, been more about regulating so-called gatekeeper platforms and online intermediaries (“big tech”) or enhancing consumer protection.

Instead, the EU needs to push much harder for a unified digital and services market that harmonizes digital laws and consumer protection regulations rather than (just) introducing new ones on top. This would allow easier scaling of digital products and help businesses operate seamlessly across European borders.

A potentially game-changing idea is to create an EU-wide legal corporate entity, simplifying the process of starting and investing in companies across the continent.5 A less fragmented investment environment for European and international investors would drive more capital into the market, create more startups and facilitate innovation and integration.

Enable its own Big Tech to emerge

It’s easy to forget that every big company was once a very small startup. Rather than enhancing, facilitating and promoting the ability of small companies to grow really big, the EU has possibly made it harder.

While it’s true that real monopolies can reduce competition, they also drive innovation. Big companies with monopoly status don’t have to fight tooth and nail for every last sliver of margin and can invest in risky ideas that often benefit everyone. They are also major employers and drivers of economic growth. Europe needs more “European Champions” that can compete globally at the forefront of technology.

Innovation before regulation

The EU should avoid big, sweeping regulations and focus on regulating actual problems, not potential ones. For example, the crackdown on AI in the US and Europe risks stifling tech development and new AI startups while further cementing the major incumbents' positions.

We all want safe technology that benefits everyone, and all technologies have externalities that need to be addressed. However, regulating rather than innovating has become the modus operandi for the EU. Over-regulating an industry in its infancy cannot be the best way forward if Europe wants to be at the forefront of innovation. The early tech industry's lack of regulation in the 90s and 2000s was arguably a key reason for its astronomical growth over the past two decades.6

In general, policies around innovation and regulations should recognize the tradeoffs between safety and growth, the necessity of market forces in generating wealth and innovation, and the primacy of long-term economic growth. In the end, a lack of progress may be much worse than any potential negative effects of particular technologies.7

Increase funding for STEM research

The goal of spending 3% of GDP on R&D should be a higher priority, as the EU average is still around 2.2% (2022). While some richer economies have exceeded this goal, most have not. In fact, the EU should aim to increase R&D spend to 4-5% across the bloc, if only to catch up.

As economist and blogger Noah Smith recently discussed, China is catching up with the US and the EU in terms of R&D spend and possibly surpassing them in applied sciences (like engineering). It’s of both economic and geopolitical importance the EU keeps up to develop its industrial capacity.

This money should primarily go to high-impact technologies and “hard sciences” like AI, robotics, semiconductors, energy, battery tech, and other "deep tech” sectors. In addition to grants or subsidies, the EU could experiment with tax incentives for companies and startups in high-risk, high-reward research and innovation.

The EU isn’t a federation and lacks a budget like a regular country. (The EU budget is mostly for internal and administrative purposes.) One solution could be for the EU to create a new centralized "EU R&D budget" separate from general EU funding. This would allow for the prioritization of key R&D initiatives at the EU level while member states maintain national R&D budgets for other purposes.

As Noah pointed out, some research indicates that high government R&D spending may crowd out private research investments. Still, as most R&D funding in the US and EU comes from the corporate sector and universities, there’s probably room for increasing government-funded R&D. Governments play a crucial role in funding risky projects and tech outside the scope of VCs, corporate investors, and universities (or as their partners).

Make English the EU's lingua franca

Today, there are 24 official languages in the EU, with French, German and English serving as “procedural languages.” Instead, English should be the lingua franca (ironic) of the EU, used as its only procedural language for official communication.

English is the most commonly spoken first and second language. The EU bureaucracy would become more efficient, and the recognition of English, and only English, as the official language, would make it a more desirable language to learn. More people proficient in English would have a big impact on the European market and economy.

This is a contentious proposal, but I think it's necessary for the EU to reach its full potential. The pride of the French and the Germans will surely take a hit. Some may worry it could marginalize other languages, leading to a loss of cultural heritage and identity. This is a downside, but ask yourself, how much do you miss the thousands of languages and cultures that no longer exist? Moreover, the idea isn’t to prohibit people from speaking their native languages but to make English the official one.

Make population growth a key policy issue

Although economists and governments have long understood the importance of population growth, anti-natalist and degrowth narratives have become increasingly popular. Overpopulation is a misplaced fear for industrialized economies. Rather, below-replacement fertility rates and declining populations are the real problem. The EU and its member governments must be clear in recognizing this, promoting pro-natalist narratives and devising policies that reverse the negative fertility trends in developed countries.

The EU should provide more legal ways for aspiring immigrants to enter and work legally, perhaps even charging for work visas (preferable to smugglers). Easily granting startup visas could make it cheaper for startups to hire from abroad. Unfortunately, the European immigration crisis has completely subsumed the conversation, focusing only on negative externalities (crime, culture clash, social segregation) rather than on the benefits (economic growth, cheaper labor, better living standards).

United in Diversity

The EU’s motto is “United in Diversity.” And it is, of course, very diverse in terms of wealth, language and culture. Nonetheless, this emphasis on “diversity"—the lack of integration and unity across the continent—is in many ways the key reason for its slow(er) rate of innovation and growth. European countries want their sovereignty more than they want cooperation and growth.

This isn’t surprising given the history of European cooperation, which was initially more about avoiding bad things (war) than a positive affirmation of what Europeans desired in the future. This is distinct from the US, which was founded in a more forward-looking spirit, emphasizing: “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.“

Europeans seem to have forgotten what made them wealthy and have been undermining their future prospects for growth. Anti-technology sentiments (regulate AI!), degrowth narratives (shut down nuclear power), ethno-nationalism/anti-immigration (Brexit), and performative equality over real progress (woke) have become the norm.

The EU needs to unite around shared values—a positive goal to strive towards—rather than uniting around what they don’t have in common. I believe that the goal should be to ensure ongoing progress (economic, social, technological) for Europeans and the world while upholding a steadfast commitment to universal human rights.

The draconian austerity measures implemented in some European countries in the aftermath of both the 2008 Financial crisis and the 2015 Eurozone crisis made a big dent in their GPD growth.

The 2006 Services Directive aimed to facilitate the free movement of services across the EU internal market by harmonizing regulations, simplifying establishment rules for service providers, and enhancing consumer rights when using cross-border services.

For being such a small country, Sweden’s arms industry is one of the most impressive in the world, and Sweden is even the world’s 13th largest arms exporter. (Which is a bit of a dilemma for a country that prides itself on being a moral role model in the world.)

The EU bureaucracy has been aware of these problems for a long time. Several initiatives have attempted to remediate its fragmentation and stagnating growth. The EU shared currency, the Euro, is perhaps the prime example of such a shared project. Initiatives have also been taken to improve the workings of the internal market for services. Many national and EU-wide innovation initiatives and organizations exist, like the EIC.

The startup advocacy organization Allied For Startups and the online Eu/Acc movement (European Accelerationism) are encouraging examples people/orgs that are pushing for these and similar ideas.

I might be cherry-picking examples, but my sense is that many of the most substantial technologies that got commercialized and reached consumers en masse started out in very poorly regulated environments. For example, during the 2000 and 2010s, many social media and Internet companies acquired customers cheaply and grew rapidly, partly because there were almost no privacy or data regulations that prevented platforms and their users from capturing or sharing data. Which in turn enabled very effective viral growth and cheap advertising. Likewise, the Large Language Models developed and commercialized by companies like OpenAI have benefited greatly from relatively open and free access to nearly all the data on the open Web. This kind of opportunity will never appear again, and it will definitely not appear in a tightly regulated market with strict privacy and data regulations. I’m not arguing that copyright and IP protections aren’t important or that privacy isn’t important. Rather, I’m saying that there are often positive externalities - broad benefits - that occur when some companies can take advantage of opportunities that may be dubious or in a legal grey area.

There are obviously exceptions where the downside risk is too high to stomach, but this is very rare. GDPR can serve as a good example of the issues surrounding heavy regulations. While it is undoubtedly good for consumers to have more power and choice in what data companies can track about them, this has come at the expense of startups and companies that have to wade through complex bureaucratic procedures and take on high legal costs to stay compliant. These stringent rules may also deter international companies from entering the European market, and diverts resources from R&D to ensuring compliance, potentially slowing innovation and growth for European tech. Ironically, the businesses the EU wanted to target the most (Big Tech) have the most resources to adapt to the regulations.

Excellent analysis.

As an American who used to live in Europe, it has been frustrating to see the stagnation in Europe over the last two decades. Europe seems to have the mindset of retirees who are willing to accept that their best years are behind them and just want to enjoy a comfortable retirement. As you said, this can only go on so long.

As for the causes, do not underestimate the importance of energy policy. Europe has extremely expensive energy prices and this takes a huge toll on everything else. This is largely due to government policy. Importing Russian natural gas papered over the problem for a while, but I think the results of trying to force a Green energy transition while phasing out nuclear are becoming obvious to all.

Given the recent EU election results, it is clear that voters know something is going wrong, but it is not clear to me that any political leaders are offering a new model based on economic growth.

Well written and interesting!

I found your essay to be informative, however one disagreement I have with its contents is your suggestion for the EU to become more innovative it should move even more towards a unified market. But I actually think that the current example of China and the historical context of the USA, two nations you compared the EU to disfavorably, suggest otherwise.

Among advanced economies, China has the most politically and economically decentralized system on earth. Local governments in China engage in partial trade protectionism, even against the rest of China. This decentralization includes fragmented capital markets and local spending that constitutes two-thirds of government spending, the inverse of the USA and EU. Local operations of state owned companies are controlled by city governments, effectively making them partially many different companies.

Similarly, the USA had a highly decentralized system for its first 150 years, with significant capital flow inhibitors between states until they began to phase them out in the late 1970s and early 1980s, fully eliminating them in the 1990s. This decentralization boosted competition, scientific advancement, technological innovation, real growth, and improved social and cultural conditions.

Historically, Europe also benefited from a less integrated market, where diverse regulatory environments spurred localized innovation and competition. Therefore, while some harmonization to reduce barriers might be beneficial, the EU should consider the advantages of reducing overall market integration. This could generate more diversified and competitive industrial ecosystems

Thanks again for the good writing, I hope you have a great weekend!

---Mike