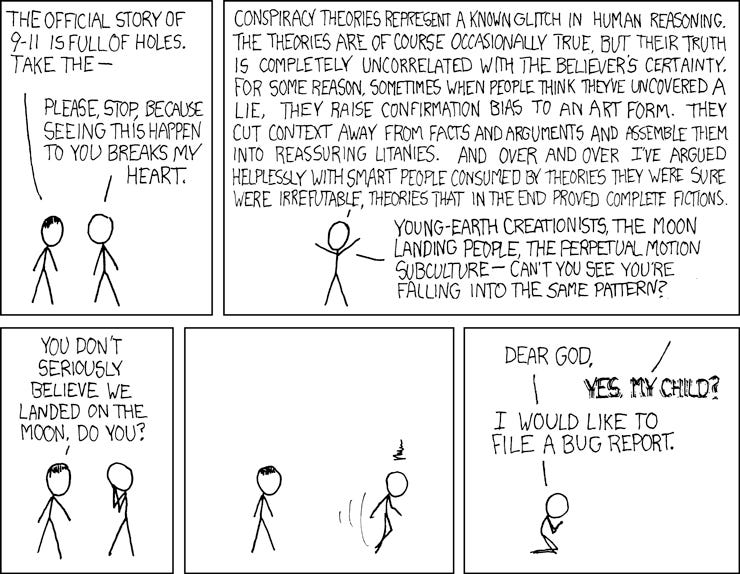

No conspiracy theory has ever been proven true

The difference between real conspiracies and conspiracy theories is the difference between good and bad explanations.

At first glance, claiming that no conspiracy theory has ever been proven true might sound absurd. After all, powerful people do sometimes conspire in secret. The key is to differentiate between actual conspiracies that have been uncovered and hypothesized conspiracies that most often amount to little more than speculation or paranoia—so-called conspiracy theories.

Although many historical conspiracies, like Watergate, have indeed happened, they are very different in both character and scope from most contemporary conspiracy theories, like the idea that 9/11 was an inside job. Conspiracy theories tend to be post hoc explanations that emerge in response to catastrophic or surprising events. They never manage to predict or expose real conspiracies. Nor do they produce any meaningful evidence that would convince independent experts or even the public of their veracity.

In contrast, when real conspiracies are uncovered, they are often exposed through rigorous investigative journalism, whistleblowers, or other intelligence gathering and are evidenced by verifiable documentation or testimony.

Despite decades of theorizing, digging and declassified documents, conspiracy theories like those about the JFK assassination have failed to materialize into anything concrete.

The difference between a conspiracy theory and a conspiracy

Conspiracy theories1 are attempts to explain certain events or phenomena by positing a secret group with clandestine intent as its instigators. They tend to be all-encompassing, broad explanations and are often unrealistically successful given the number of people and organizations involved.

A conspiracy is an attempt - successful or otherwise - by two or more people to achieve some usually secret goal in an unlawful or harmful manner. In contrast to conspiracy theories, real conspiracies are rare, limited in scope, and are usually uncovered through rigorous investigation.

In a conspiracy theory, the conspirators are endowed with extreme levels of competence, far-reaching planning capabilities and perfect secrecy. The role of unintended consequences, chance, and incompetence in explaining events is dismissed.

The “evidence” provided supporting the theory is largely circumstantial or based on gaps in the official story. Any evidence contradicting the conspiracy theorist’s narrative is seen as deliberate attempts by the conspirators to manipulate the public; any absence of evidence is seen as proof that “they are hiding the truth.”

When one points out the lack of credible evidence in support of a given conspiracy theory, one is often met with an accusation of naivité, in believing everything the “government” or the mainstream media tells you. The conspiracy theorists will claim that they “have done their own research,” which usually involves watching a lot of YouTube videos.2

There’s a certain style to conspiracy theories that’s easy to spot once you’ve seen enough of them. It’s not just that something contradicts the mainstream narrative or that it spreads on X/Twitter. For example, the lab leak theory of the origins of Sars-Cov-2 is a perfectly reasonable idea, prima facie, given that there is a virology lab in Wuhan that conducts gain-of-function research and because there’s always some risk that novel viruses may escape the bio labs. But when you claim that the virus has been engineered and leaked on purpose to achieve some sinister goal, you're quickly leaving the realm of plausible speculation and venturing into the lands of conspiracy theorizing.

What most conspiracy theories have in common is that they start with a conclusion and work backward from there, looking for evidence (mostly gaps) that creates a plausible account of the story the conspiracy theorists already believe. This approach is the opposite of scientific inquiry, which starts with an observation and builds a theory that can be tested. Conspiracy theories, however, begin with a theory and then selectively gather evidence to support it. Most often, the conspirators are thought to be a large, faceless organization or shadowy cabal. “The government,” “the Jews,” “the CIA.” In real conspiracies, the perpetrators are often a small group or part of an organization, rarely involving more than a handful of people.

Right after the (first) assassination attempt of Donald Trump in Pennsylvania on July 13th, a flood of different conspiracy theories started emerging to explain the spectacular security failure that enabled Thomas Crook to nearly kill Donald Trump. Depending on your particular political bias, you could find any number of satisfying explanations as to who was actually behind the shooting. Although we may never know, conspiratorially minded people started throwing out explanations even before the gun smoke had cleared. This is a tell-tale sign of a conspiracy theory, as opposed to an actual investigation.

Much like any good scientific theory, a good conspiracy theory must be falsifiable. That is, it must be specific enough such that there are some objective criteria with which we can assess under what conditions it can be false. “Vaccines are bad” isn’t a theory. Some people who take vaccines get side effects; some vaccines may produce more side effects than others. This does not constitute proof that Big Pharma is deliberately creating vaccines that make people sick or that Bill Gates is trying to control people by implanting 5G chips in them.

Conspiracies, real and imagined

The standard retort to the claim that “no conspiracy theory has ever been proven true” is to point out the many real conspiracies that have been uncovered. Indeed, there are many of those, and likely many more we will never know about. Governments and other institutions sometimes lie, and there are always some unanswered questions about any given event, so there will always be room for more or less plausible conspiracy theories to explain them.

So, what do I mean when I say that no conspiracy theory has been proven true?

No conclusive evidence, whether in the form of testimony or documentation that can verified by a neutral third party, has ever been put forth to back up the specific (falsifiable) claims made by various conspiracy theories about the nature of the events they attempt to explain.

Although conspiracy theorists will point to “evidence” like voice recordings, pictures, videos or documents about or related to the event that seems suspect or leaves questions about some person or organization’s involvement unanswered, collectively, it doesn’t constitute proof of the broader claims made by the conspiracy theory. This is why courts or other public institutions have never vindicated any of them. As explained above, conspiracy theories are often characterized by a strong reliance on filling in gaps and jumping to conclusions rather than actual evidence.

There are many examples of historical “true conspiracies” levied to defend the plausibility of conspiracy theories in general; some common ones I’ve come across are the Tuskegee experiments, Operation Northwoods, COINTELPRO, and MK-Ultra, to name a few.3

Tuskegee Syphilis Study. The Tuskegee Experiment was a government program that ran from 1932-1972 where the US Public Health Service studied the natural progression of syphilis in several African American men without their knowledge or consent. The participants were withheld treatment even after it was possible with the discovery of penicillin. Although this was unethical, it’s debatable whether it should be considered a conspiracy. The study was never secret, as research reports were published in (public) medical journals.

Operation Northwoods (1962). Operation Northwoods was a proposed false flag operation meant to justify a military intervention in Cuba. Some senior military leaders proposed various false flag operations, like a staged shoot-down of US military aircraft outside the coast of Cuba, even “terrorist” attacks across some US cities and other shady stuff. President John F. Kennedy rejected the idea. Conspiracy theorists often point to this as an example of what the US government/CIA is “capable of.”

COINTELPRO. COINTELPRO was an FBI program that spied on and disrupted domestic political organizations, civil rights groups and so on during the “Red Scare” of the Cold War. It was an illegal program that was exposed in 1971 when documents were leaked after a group of eight men broke into an FBI office and took the documents. Clearly unethical and illegal, and an overreach of the FBIs publicly stated mission, but not completely outside the realm of what a federal law enforcement agency might consider doing.

MK-Ultra. From 1953 to 1973, the CIA ran a program to develop interrogation techniques and discover drugs that would enable “mind control” and force confessions, using brainwashing, psychological torture and the administration of drugs like LSD. These illegal and unethical experiments were often conducted without the subject's consent. It's definitely one of the most conspiracy theory-esque secret programs to have been exposed.

What all of these conspiracies have in common is that they were eventually uncovered through formal investigations, whistleblowers, and leaked documents. Unlike modern conspiracy theories, they did not start as speculative theories but as secret programs or clandestine operations that came to light through the disclosure of hard evidence. There was also no conspiracy theory about them before or during the time that these programs or events were happening. Only after the public learned about them did they become part of the “conspiracy theory canon.”

It’s also debatable whether some of them are technically conspiracies, in the sense that they were secret and illegal plots by some group of people, unbeknownst to the public. For example, the Tuskegee experiments were more a reflection of the unethical academic and medical practices and the racist attitudes of the time than an actual conspiracy.

Another revelation that vindicated many conspiracy theorist’s paranoia was Edward Snowden's series of leaks about the NSA’s intelligence gathering apparatus: The Snowden Files.

In June 2013, Snowden, then an NSA contractor and intelligence analyst, disclosed thousands of secret documents by sharing them with a handful of journalists. Over the course of several months, they published them across multiple media outlets like The Guardian, Der Spiegel, and The New York Times, among others. The classified documents revealed a “global surveillance apparatus” much more extensive than most people thought existed. It exposed the detailed nature of specific NSA programs like PRISM and XKeyscore, as well as how the NSA used commercial telecom and tech companies to access their communications traffic or data. It also showed how US intelligence agencies used these programs to spy on foreign leaders, including allies like Germany. The legal status of the NSA’s and other intelligence agencies’ surveillance programs is still debated, but it’s clear that it was at least partially illegal.

Snowden was not the first whistleblower to reveal information about the global intelligence and surveillance apparatus. Prior to Snowden, both independent journalists and whistleblowers from within the US and British intelligence services had already disclosed information of a similar nature.

The disclosures seemingly proved that "Big Brother" is always watching us (and that using tin foil hats maybe isn’t so crazy after all). Yet, before these revelations, there were no specific conspiracy theories that had accurately predicted the nature and details of the “global surveillance apparatus” in the manner Snowden revealed. There were, of course, broad suspicions of government surveillance and plenty of conspiracy theories about the NSA, CIA, MI5, and other intelligence agencies in general. However, in contrast to such theories, Snowden provided detailed, verifiable evidence that could withstand scrutiny.

The Snowden Files exemplify another aspect of the difference between real and hypothesized conspiracies. In most conspiracy theories, the public appearance of the organization is thought to be a lie, and its true aims are the opposite of its stated purpose. In contrast, when real conspiracies are exposed, it confirms what everyone already suspected; the conspirator's actual behaviors are about as bad as you’d expect. (The NSA really is listening!)4

If you believe that “governments and powerful people are always conspiring behind closed doors,” you will be vindicated over and over again. But it is hardly surprising to anyone that people in power do many things they don’t want the public to know about. This doesn’t make conspiracy theories true in general. The problem with conspiracy theories is that they try to explain too much.

Conspiracy theories fail to convince

There are an endless number of conspiracy theories out there: the 9/11 attacks, the Moon Landing, the New World Order, the Freemasons, Big Pharma, Vaccines causing autism, Qanon, and probably every presidential assassination, to name a few.

One of the most famous conspiracy theories concerns the idea that 9/11 was an inside job, which became popular in part through a series of captivating video “documentaries” during the early days of YouTube5. The “9/11 Truth” movement posits that the U.S. government (or parts of it) orchestrated the attacks as part of a broader agenda to justify the wars in the Middle East, take its oil, and increase government surveillance.

The attacks on September 11th, 2001, where two hijacked planes brought down the World Trade Center (WTC) towers and another one crashed into the Pentagon, were indeed a conspiracy. It was just not a false flag by the government, but a terrorist attack orchestrated by a well-funded group of Wahhabi Islamists motivated by global jihad and other geopolitical grievances.

How do we know this? Not only did Usama Bin Laden and al-Qaeda take credit for the attacks, but they also carried out the 1993 bombing of the North WTC tower garage and many others. The CIA and the FBI also had prior knowledge of an impending attack and were monitoring some of the people involved but failed to stop them (most likely due to a failure to coordinate intel). Moreover, plenty of physical evidence and other documentation, compiled by both the official 9/11 Commission Report and independent investigations, shows which people were involved, how they planned and executed the attacks, and so on.

Given this and the lack of concrete evidence for the hypothesized false flag, the explanations offered by the conspiracy theorists fail to convince. Like most conspiracy theories, there are plenty of facts, but the conclusions are wrong because they’re based on half-truths, misunderstandings, wild guesses, or leaps of logic. The 9/11 Truth theory points to things like the interaction of steel constructions and burning jet fuel, the way the buildings collapsed, and the lack of debris from the planes, among other things, as "evidence" that the official story is false and that it was actually a controlled demolition.6 Needless to say, plenty of independent experts have thoroughly debunked these claims, explaining the collapse (using sound engineering principles and evidence) as a structural failure caused by the planes’ impact and subsequent fires.

Don’t attribute to malice what can be better explained by incompetence

Of course, this doesn’t convince the “truthers,” who can easily dismiss the explanations and claim it’s all part of the government’s attempt to cover up the truth. Indeed, there will always be many details or facts that remain unexplained, casting doubt on the official story in the eyes of the truthers. But this kind of explanatory acrobatics makes the theory effectively unfalsifiable - a hallmark of typical conspiracy theories and bad explanations.

The Umbrella Man at the JFK assassination is a particularly illuminating example of how many seemingly weird and suspicious details nevertheless turn out to be completely innocuous. On November 22nd, 1963, the day JFK was assassinated in Dallas, a man with an umbrella can be seen in videos standing close to where the cars passed as JFK was shot, which was weird given that it was a perfectly sunny day. Conspiracy theorists assumed that the Umbrella Man was somehow part of the plot, but the truth was far more mundane. In a hearing many years later, the Umbrella man himself - Louie Steven Witt - explained that he was holding the umbrella as a symbolic protest against JFK’s father, Joseph P. Kennedy Sr., who had supported British PM Neville Chamberlain's nazi appeasement; Chamberlain often carried a black umbrella as a fashion accessory. Conspiracy theories thrive on this kind of non-evidence because it lends itself so well to speculation.

I’m not saying that any claim about sinister conspiracies on the part of governments, big corporations or other powerful people should always be dismissed outright. Or that no conspiracy will ever be proven true (in the future). After all, it’s not impossible that some organization manages to pull off a really impressive, large-scale plot with no leaks or mistakes. However, given the complexities and unexpected nature of most events conspiracy theories try to explain, the difficulty of coordinating multiple people or organizations in secret, and the historical lack of evidence for any conspiracy theories, our priors should be calibrated accordingly.

Conspiracy theorizing

Contrary to what many assume, belief in conspiracy theories is not based on a lack of knowledge per se; conspiracy theorists are very well-informed on the specifics. Instead, it’s more of a pattern of belief and identity.

Believers often have a tendency towards paranoid thinking and Machiavelianism, distrust of authority, and feeling a lack of control in general, which are all things that correlate with believing in conspiracy theories. People who strongly believe in the truth of one conspiracy theory also believe in many others, even though they may be factually inconsistent with each other, taken together. But this isn’t surprising when you see them as representing the believers’ general attitude toward the world.

Conspiracy theories can be associated with particular political beliefs, and research shows that psychological traits and right-leaning political views, like support for Trump, are linked to a higher belief in conspiracy theories. However, this hasn’t always been true. A consistent finding is that people who lack political power are more likely to believe conspiracy theories about those who have it. As political parties or alliances from across the political spectrum move in and out of power, belief in conspiracy theories about the “ruling elite” will shift alongside it.

Conspiratorial thinking is also part of a broader class of erroneous beliefs like superstitions and fallacies. There are many conspiracy theory-adjacent ideas, like those about the extraterrestrial origins of UAPs (UFOs), paranormal experiences, and belief in mythical creatures like Bigfoot, that aren’t strictly conspiracy theories but that share a lot of the same traits.

Of course, pointing out any of this does not quell the conspiratorial mind. Quite the opposite.

Conspiracy theorists urge us to “open our eyes” and “connect the dots.” In pointing out the lack of evidence or consensus, you are dismissed as either close-minded or naïve. The believers are humble and open-minded; they’re “just asking questions.”

It’s not always unreasonable to be skeptical of official accounts, to question “consensus narratives,” and to believe that governments and powerful organizations have and do hide things from the public. Still, none of the strong claims made about the 9/11 conspiracy theories, or any others, have ever been conclusively proven. They remain in the realm of speculation.

In principle, I remain open to the idea that some may be “exposed” in the way the conspiracy theorists imagine, though I find it extremely unlikely. It’s not the kind of thing that keeps me up at night.

Do you agree or disagree? Have any counter-examples I’ve failed to consider? Please do share!

When defined strictly as a theory about a suspected conspiracy, a conspiracy theory is not outlandish or implausible per se. A police officer or journalist investigating a suspected conspiracy or criminal plot has developed a theory—in the colloquial sense of the word—about that event or plan. Nevertheless, this is not what most people mean when they think about a conspiracy theory.

Of course, there’s nothing wrong per se with non-mainstream content on YouTube, X, or the Internet more broadly. I consume a lot of it, in addition to regular news from the MSM. Substack is full of unique, interesting and important content that veirs far outside mainstream conversations. It always comes down to the content itself rather than the platform or medium. But there’s a reason why actual conspiracies are exposed by rigorous, often dull, investigative work like reading lengthy documents and reports and not by watching amateur documentaries on YouTube.

I’ve learned about many supposed conspiracy theories from Brian Dunning, who runs skeptoid.com. As a side note, it’s struck me that a lot of the conspiracy theories we tend to hear about in the West are almost always about the US or the Jews.

I credit this insightful observation to Scott Aaronson: https://scottaaronson.blog/?p=1596

In 2007/2008, I went down the rabbit hole of 9/11 conspiracy theory videos on YouTube and became enthralled by the idea that it could be an inside job. I was naïve and eager to learn. Luckily, the more I read, the more unsure I became, and I finally managed to find saner explanations. Eventually, I abandoned the conspiracy theory, which took me down the opposite path of scientific skepticism and becoming the shill of Elite Propaganda I am today.

If you’re unfamiliar with the 9/11 conspiracy theories, there’s plenty of juicy content on YouTube. Viewer discretion is adviced.

The thing about conspiracy theorists is they tend to be the type of people who will never admit they are wrong. The amount of otherwise seemingly well educated rational people who try and convince me the moon landings were staged is quite incredible. When I reply: you do know that the US was in a race with the Soviets and they were able to track to the Apollo spacecraft all the way to the moon and back. Do you not think if it was faked the Soviet Union would have been the first to jump up and down and cry foul - rather than having to wipe egg off their face?

Oh yes I'm told, but they were complicit in the conspiracy also!

While I don’t disagree with your overall conclusions, I am not sure that conspiracies by your definition are all that rare. In fact, I think that it is quite common. It is really a form of cooperation between two or more people that other people deem as bad or immoral.

People are always scheming for their own benefit and engaging others in their plan. Every organization has a large number of them, particularly in management. Gossip is the most common form, and that gossip often leads to a person gaining an advantage over another.

The key factor is the overall impact to the rest of society. 99.9999% have little impact on the rest of society so no one calls it a conspiracy. When it has a big negative impact, then people call it a conspiracy. When it has a big positive impact, people call it “visionary leadership.”